by Leena Kurvet-Käosaar.

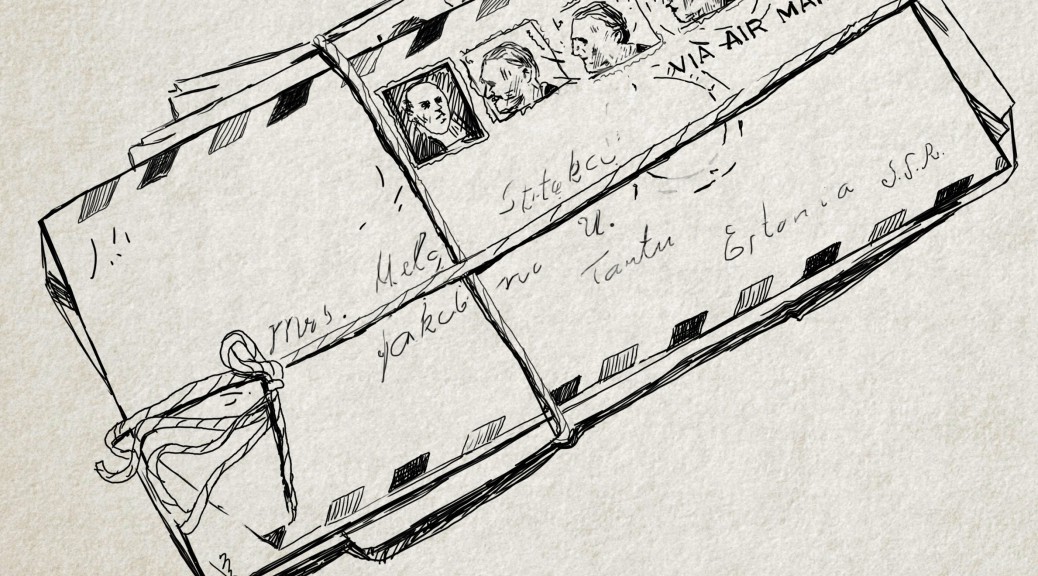

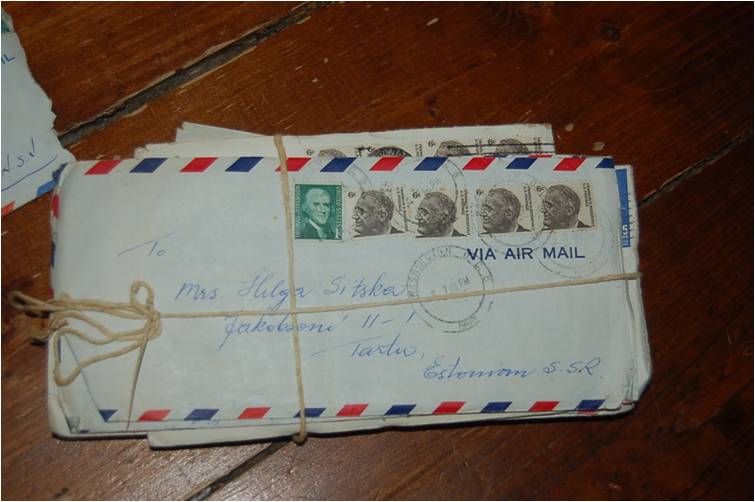

The case study is based on the correspondence across the Iron Curtain of two sisters, Helga Sitska (1914-1989) and Aino Pargas (1922-2000) between Estonia (then the Soviet Socialist Republic of Estonia) and UK and the USA. Helga Sitska was my maternal grandmother and Aino Pargas my greataunt. Their correspondence, both sides of which have been preserved, consists of approximately 450 letters, cards and postcards. The correspondence is today preserved at the Sitska family home in Tartu and kept by my mother. I have her approval to use the correspondence for research purposes.

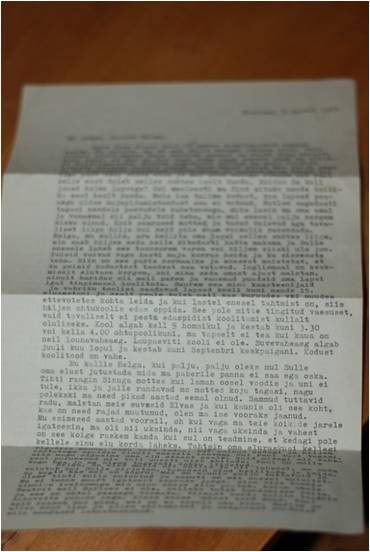

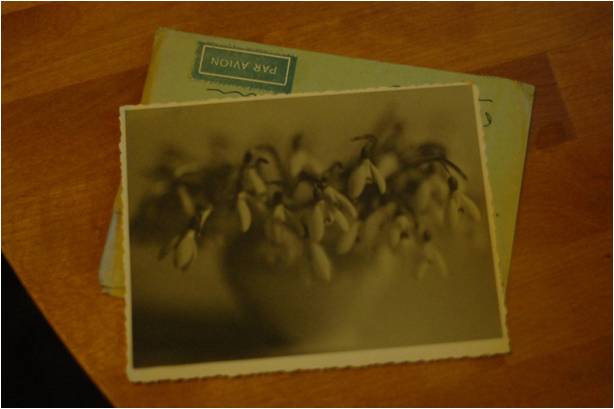

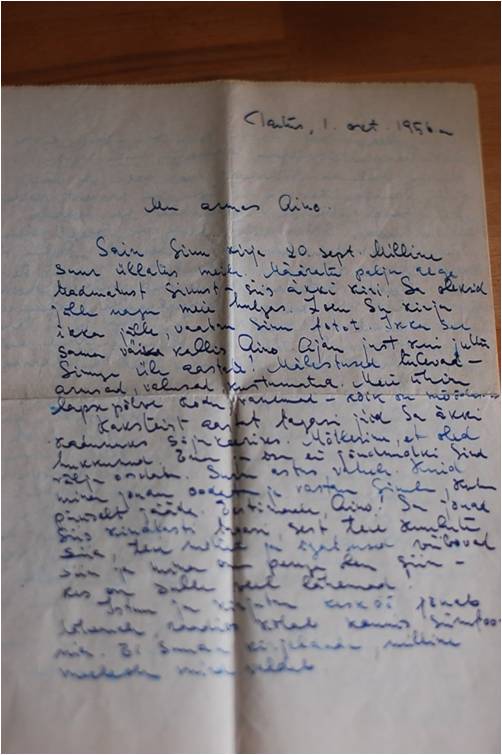

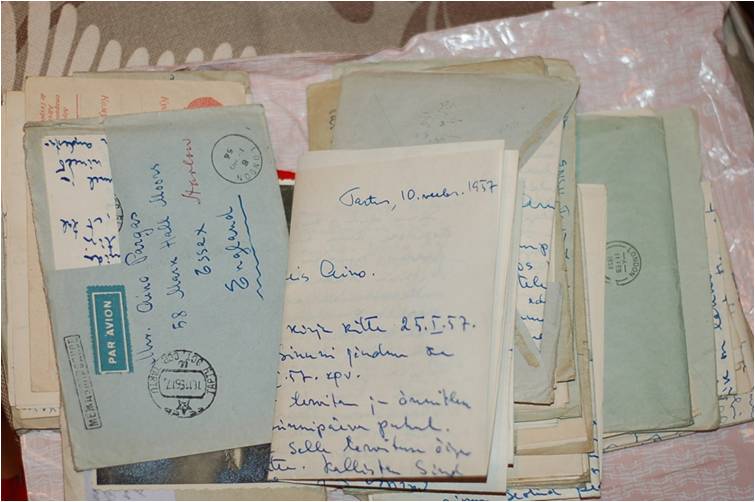

Illustrative material: photos of the letters and envelopes, photos of Helga Sitska and Aino Pargas. For ethical reasons, all photos of the letters have been taken so that the text of the letter in unintelligible. The contents of the letters is mediated only via a selection of translated quotes.

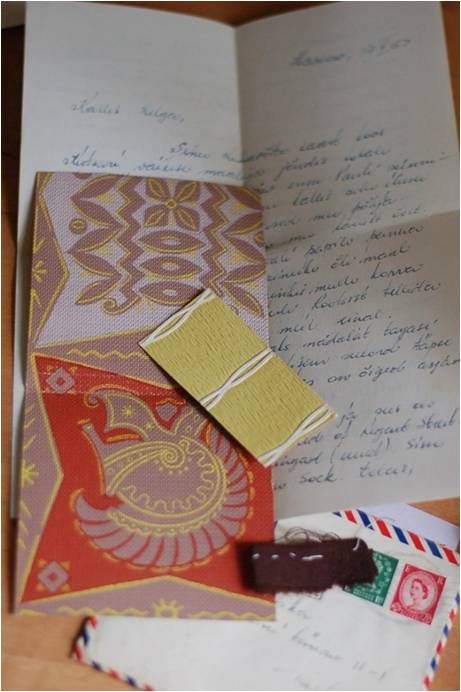

Aino’s livingroom wallpaper samples

Aino’s livingroom wallpaper samples (this should also go with question nr 3 where I discuss how the sisters maintained a close bond by sharing their everyday life experience with each other)

Photo 7: Aino and Helga in Washington DC. In 1969, the first time they met after parting in 1944 (here I would like to add excertps from Aino’s letter where she wirtes about her last memory of homw and her mother before she left Estonia in 1944.)

Work in progress on the letters.

(My) work in progress on the letters, systematizing, identifying themes (This would go with a section where I talk about my work process on the letters, also problems and difficulties

My great-aunt Aino Pargas (1922-2000) fled Estonia in 1944, after the war settled down in UK, moved to the US in 1958, lived most of her life there Maryland and worked for the Library of Congress. Aino’s husband was a German POW in the Soviet Union for 6 years. They reunited in 1950.

My maternal grandmother Helga Valgerist-Sitska (1914-1989) studied law at the University of Tartu before WW II, had three children, and was for many years considered unemployable for political reasons by the Soviet regime. Gradually, she found employment in the field of the Soviet equivalent of real estate law and worked for Tartu municipal goverment. It is not possible to completely identify the exact beginning of the correspondence between the sisters. Among the preserved letters there are some letters by Helga Sitska to Aino Pargas from the year 1948 that were among Aino’s possessions, yet there are no responses to Helga. Most probably Aino’s letters were confiscated by the Soviet authorities or she did not reply to them. Systematic correspondence started in the late summer or fall of 1956 and continued until the spring of 1989 when Helga Sitska died.

As travel into and from the countries behind the Iron Curtain was severely restricted, the sisters were able to meet only a few times during their whole lifetime and letters became their primary medium of communication, the sole vehicle for the intimate dynamics of sisterly affection, where lives lived on two continents in vastly different sociopolitical and material contexts were not only represented through the correspondence, but in a way lived within the possibilities and boundaries of the medium. The correspondence makes visible different agendas and influences (sociopolitical, family-oriented, national, gendered, intimate) that intertwine and shape the correspondence and ultimately the nature of the relationship itself.

As such, the correspondence is far from exceptional as for thousands of families who were separated by the World War II and the change of political regime in Estonia this was a common (and the only available) means of keeping during the Cold War period. Such correspondences have not been systematically collected by Estonian memory institutions. However, for instance the Archives of Cultural History in the Estonian Literary Museum preserve various ‘across the Iron Curtain’ correspondences between men and women of letters and public intellectuals. Taken together, these correspondences provide valuable information about possibilities of communication during the Soviet period, level of trust that was established between the corresponding parties, ways of dealing with issues of censorship, etc. From the more narrow perspective of family history, the dynamics of correspondence between family members is of primary interest. However, correspondences between family members are not widely available for research or other kinds of public use. Firstly, at the present moment, many the corresponding parties have died and the correspondences may not have been preserved at all. The preserved correspondences are in family archives and cannot be accessed for research purposes. The current correspondence therefore constitutes a unique textual evidence of dynamics of communication across the Iron Curtain, yet this it is important to bear in mind that this correspondence is also part of a family archive and can (selectively) be accessed only because of the overlapping of different positions that I represent: that of a family member and that of a researcher.

The correspondence provides rich and multifaceted insights into different strategies of developing and maintaining sibling intimacy. Intergenerational importance of the letters for strengthening family ties can be seen in the text of the letters themselves as well as the reading process and reception of the letters in my family. In the letters, the sisters use past memories of their childhood and youth and memories of their parents to build up and maintain a close bond with each other. Through the letters a family bond is also created between Aino and Helga’s children (Aino had no children of her own). Helga provides detailed updates of the lives of her three children to Aino and Aino responds with comments to Helga as well as with letters and gifts to her niece and nephews. Later, my generation was also successfully included in the correspondence.

Intercultural aspects of the correspondence include the ways in which the sisters mediated their lives in two very different political systems to each other, an aspect that, at least over the first years, was subject to Soviet censorship and awareness of this can be traced in the letters. In her letters, Aino provided detailed descriptions of her life in UK and later in the US, focusing not only on her life but also on society and culture at large, way of life, fashion, nature etc. Although Estonia and Tartu were familiar to Aino, in her letters, Helga strove to describe the changes that had taken place during the war and the following years. Both sisters often rely on familiar places, attitudes and aspects of life and then proceed to elaborate on a new experience or a change. Over the years, when Aino settles down comfortably in Maryland in the USA and starts perceiving the US as her home, a tension is created between the sisters as Helga, my grandmother finds it impossible to accept that any other country than one’s native land can be called home.

Here I try to include some brief examples of different aspects of the correspondence and elaborate on them

In one of her first letters my grandmother writes:

A Bundle of Aino’s LettersYour letter arrived on Sept 20 (1956). What a wonderful surprise: all these long years of silence and now, at last, your letter. …Twelve years ago you were suddenly lost in the turmoil of war. We thought that you had perished … I sit here and write as the midnight is drawing near and a beautiful symphony is playing on the radio. No words can describe how I feel. What can I write in just one letter? I should write a book, not a letter.

On October 22, 1956, Aino reponds to Helga:

Grandma’s First LettersIt is so hard to believe that after so many years I am receiving a letter from home again. I am looking again and again at the photos of you and your childrenand no words can express how dear you are to me.

As the sections of quoted letters demonstrate, a strong desire to reestablish and recover intimacy between the sisters can be found already in the very first letters. Over the years, the correspondence developed its own textual strategies for creating intimacy and its evolvement in time makes visible the ways in which the epistolary medium catered for the needs of maintaining and developing these intimate exchanges as well as where it seemed to have failed. From my readings of mostly the letters of the 50’s and 60s, three main different strategies of creating intimacy have emerged:

1) reliance on common memories

2) verbal confirmation of closeness that also involves epistolary exchanges concerning photos

3) different ways of familiarizing each other with the details of everyday life and with the cultural contexts of their life.

Here I add examples and themes, e.g.

1) reliance on common childhood memories,

2) ways of integrating Aino into Helga’s family life

3)ways of sharing everyday life,

4 mediating cultural change (Helga) and specificity (Aino)

This resource can be used for different pedagogical purposes for different levels of education, yet the purpose would be roughly the same:

to promote awareness of one’s own family history,

to encourage people to conduct research into their own family history,

to identify new sources and to frame them both in immediate familial context as well as wider cultural contexts.

The source can be used to demonstrate that the concept of the archive is not limited to official national memory institutions but can be used in more fluid and informal contexts within the framework of one’s family.

Description how the resource could be used for teaching/learning purposes

A Bundle of Helga’s letters

Here I will add a description how the resource could be used for teaching/learning purposes. It will be more or less one task to start with – to think about and to look for/ask for family documents and sources that facilitate intergenerational and intercultural exchange.

For university level teaching, the task would be to think about more general theoretical issues concerning intimate recording and reading of lives and see if and in what manner these relate to students’ own family histories.

For adult/museum education the focus could be on one kind of source – the letter or the correspondence and the during training, participants would be shown examples of different family correspondences and correspondences across the Iron Curtain.

The training could consist of two sessions: one where they are familiarized with that type of source and the second where they find similar sources within their own family and discuss the process of looking for them, what they have found (also what could not be found) and the importance of the sources. Along the same lines, a training session can also be organized for schoolchildren but the explanations and tasks should be simpler.