by Maija Runcis.

One way of studying everyday family life in Soviet Latvia is to use records from people’s court in the Latvian state archive, especially files on divorces. In these files you can find information on families living conditions, housing, relations and emotions.

This is one transcribed case from October 1961, (file no 809, Fond 856, the Supreme Civil Court; first instance People’s court). It is a handwritten inquiry from a man to the People’s Court of Riga city, Lenin district:

Application!

In 1947 January 25th my wife and I were registered as married at the city office in Riga. Our son who lives by his mother was born in May 1952.

It has been dissentions in our marriage since 5-6 years and it has been a lot of controversies between us. The conflicts started and developed mainly because of my wife’s bad nature and her subjection to her relative living in our apartment, and their bad gossiping against me. My wife accuses me constantly with unreasonable arguments causing new quarrels, which had forced me twice to leave her and live separate from my family. When I built our family house, I hoped that when it was built we could improve our relationship and live together. However, nothing went better. Our relationship continued to be bad even after we had built our family house and the quarrelling went on, so I left my family and broke off from my marriage for more than a year ago and it has not been renewed since that. My wife’s relatives are also living in our family house and they support her in her aggressiveness against me.

I am convinced that our relationship has no possibilities to be repaired or normalized and we have to walk our own way separately and finish our common life, divide our common household and our family house in two ideal parts.

Cultural and historical context for the source.

In 1944, the same year when the Soviet Red Army occupied Riga, Latvia got a new legislation on family and marriage. Only registered marriages were recognized to be legal, and divorce became subject to the court’s discretion. Children born out of wedlock were not guaranteed maintenance from the father and fathers had no rights and obligations vis-à-vis their children. According to the 1944 decree, biological fathers were not registered as such on the child’s birth certificate unless they were officially married to the mother. A lot of men left their partners for new ones, but without officially divorcing and remarrying. This law was in force until 1968.

It should be noted that the family decree had a very significant impact on people in general, not only children. Divorce and its consequensis was something that could materially and adversely affect the divorced couple’s career. The Communist Party organizations controlled each single divorce; they examined cases of drunkenness, negligence of children, and infidelity. For those who were not party members, these functions were performed by the local trade union workplace committees.

In the case above the husband divorced officially but he stayed in the same house because of housing shortage in Riga. The family lived in Riga in their own house with three rooms, all together 52 square metres. The household exists in 1961 from wife (43 years), husband (48 years) and a 9 years old son, and the wife’s relatives (it is not clear how many persons). The husband was unsatisfied with the family situation and he wanted a divorce, mainly because of conflicts between him and his wife’s relatives. In a letter to the People’s court he complained about the limited living space for him and his family and he asserted that the relatives didn’t like him.

From the court’s file we do know that he had met another woman (letters to the court from his wife) and we also got information on how the house was furnished and equipped.

Extract from a letter to the Supreme Civil Court from the husband:

During our marriage we built a house in Riga, Sejas iela nr 20, one floor house existing from three rooms, 52,82 square metres, worthy 3 928 roubles, and an outhouse worthy 380 roubles, all together worth about 4 308 roubles.

More over we bought during our marriage a “foreign” trademark piano, worth at least 500 roubles. The property can be distributable between us as follows:

- The ownership of the house should be parted in two equal ideal parts;

- The piano I agree to leave to my wife if she pay me the half of the piano worth because this is not u subject that could be divided in practice.

The husband leaves the purchase from his following goods.

One twin-bed 130 roubles (rbl), writing-desk 40 rbl, bookshelves with bookcase 40 rbl, table, 30 rbl, cupboard 20 rbl. From our common life when married I’ve got nothing.

Relevance of the source for the study of family history in terms on intercultural and intergenerational aspects.

Among scholars, archival documents and records have been seen as passive resources kept in state repositories to be exploited for various historical and cultural purposes. Seen from another perspective – within the interdisciplinary field of memory studies – archives have been viewed as critical and problematic components of memory. In the context of wide-ranging social and legal systems this perspective has also highlighted the connection between archives, human rights advocacy and efforts to secure social justice. Looking at archives and records from a postmodernist perspective, however, we determine a more complicated picture. From this point of view, archives are established ‘by the powerful to protect or enhance their position in society’. In this sense archives are a tool for the powerful to control the individual and our common past. As a researcher, I have to be aware of these power relations as well as the multiple provenance of the archive: what kind of society created these documents, and what information do they provide about the social society of the past? What kind of relationships between the creators of the archives and society are visible or tacit in the archives?

From an ethical point of view, the use of public archival documents needs to be considered carefully. The Soviet archives mostly contain the holdings of official public bodies, but these papers also contain mention of a great many personal names and information about individuals who today, in post-Soviet society, might be completely opposed to the idea of being reminded about their past.

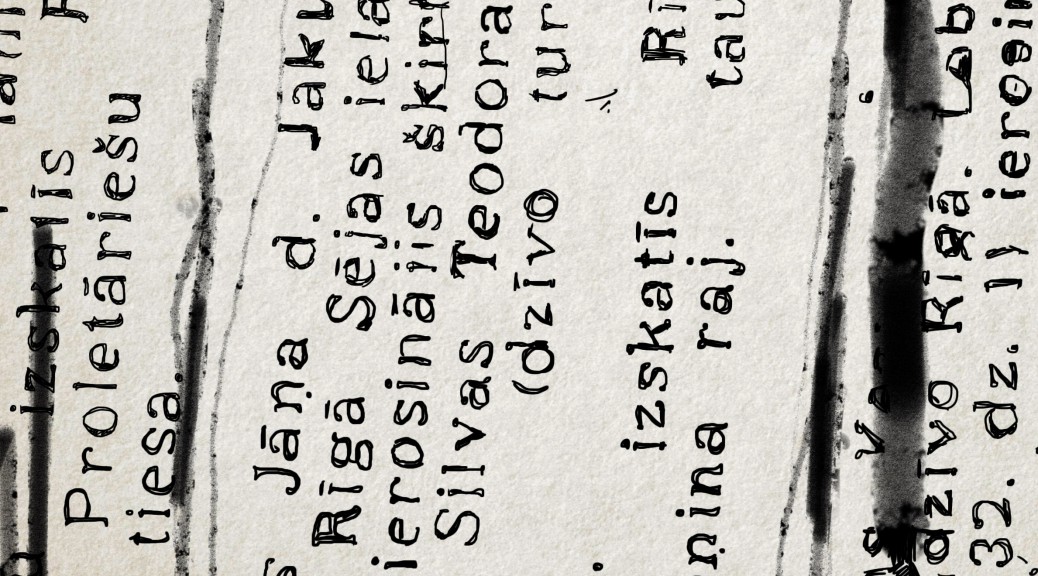

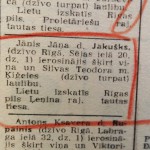

The first photo is the decision on the house dividing; the second one is a handwritten letter from the wife to her former husband and the third one is a notice in the newspaper that informs about the divorce between the couple.