by Jyrki Pöysä.

In the Northern corner of the city of Joensuu stands a sad representant of the local history of this small eastern Finnish town: the empty buildings of former restaurant-hotel Jokela and cinema Kino-Karjala.

Jokela in its present state; Photo Jyrki Pöysä

During its more glorious times the building was one of the centers of the Joensuu cultural and business life: journalists and local business men used it as a regular meeting place. Among the visitors to the hotel-restaurant are also said to be the front-row Finnish musicians and film people. (As an important source about the glorious times see the book Wanha Jokela (2002), which is a result of the oral history project by Jyrki Piispa and Eino Maironiemi; the interviews made by the project are archived at the Finnish Literature Society’s Joensuu Tradition Archives.)

From 1970’s up to the closing in the end of 2012 the restaurant was an important meeting place for local and national artists (musicians, writers etc.) and the university people (students, teachers, professors) of the small but fast growing University of Joensuu (about the oral history of the University of Joensuu see Makkonen 2004). During its last years the hotel-restaurant, called then Wanha Jokela (‘Old Jokela’), became also part of the local conflict about the importance and costs of saving urban heritage.

Local conflict of values: saving the restaurant; Photo: Jyrki Pöysä

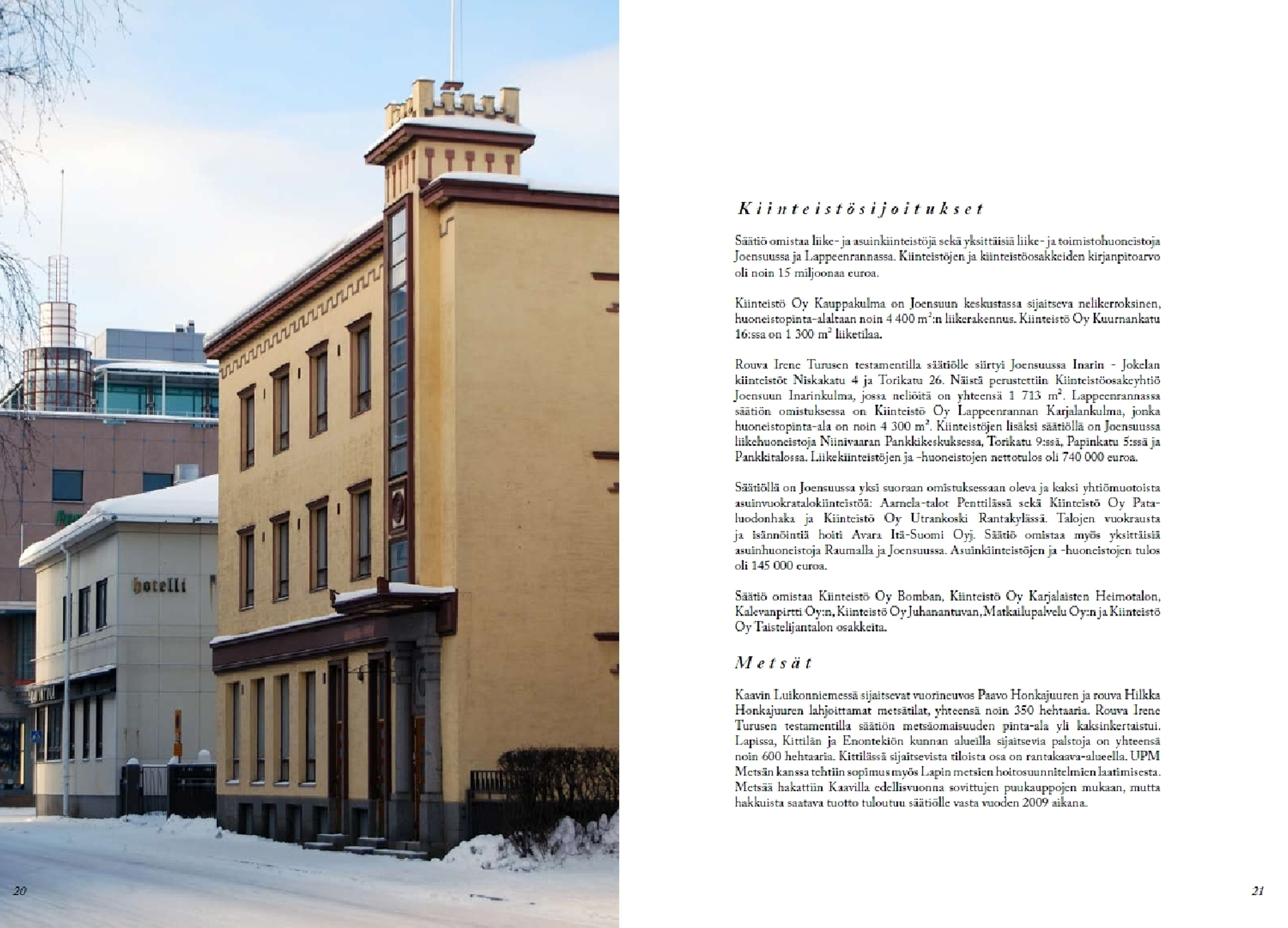

Hotel-restaurant-cinema complex was owned and led by one family, the Inari-Turunen families. The ”first” member of the family and the founder of the family businesses was Heikki Inari (b. 1891). After his school years in Joensuu he worked at the Russian railroads up to the Finlands indepence in 1917. Before the October Revolution he was also working at the Finland’s Station in St. Petersburg. During these years he met his wife Maria Pauloff (b. 1894), who was a Russian by origin and who was educated in the famous Smolna girl school in St.Petersburg. The history of the Inari-Turunen family was not only a success story, but also a family tragedy. Heikki and Maria had only two children, son Olavi (b. 1921) and daughter Irene (b. 1925). Olavi died in the end of the second world war, at the age of 23. Olavi had participated the war as a volunteer.

The family of Heikki Inari having a dinner with other relatives or friends, Maria, Olavi and Irene on the right side of the table; photo published with a permission from the North Karelian Museum).

Irene was married in 1948 to an important Finnish choir leader and an economist Martti Turunen (b. 1902) who was then almost twice her age.The couple was childless: regardless of international specialists they could never get children to take hand of the family businesses. During their marriage Irene and Martti were living in Helsinki. After the death of her father Heikki in 1961 Irene had to take care of the family businesses, together with her husband Martti.

Maria (in the center), Irene (nearest to the right corner of the table) and Martti (on the utmost right) together with the restaurant workers having a party 6.11.1967; Photo from Anita Latola’s private archives

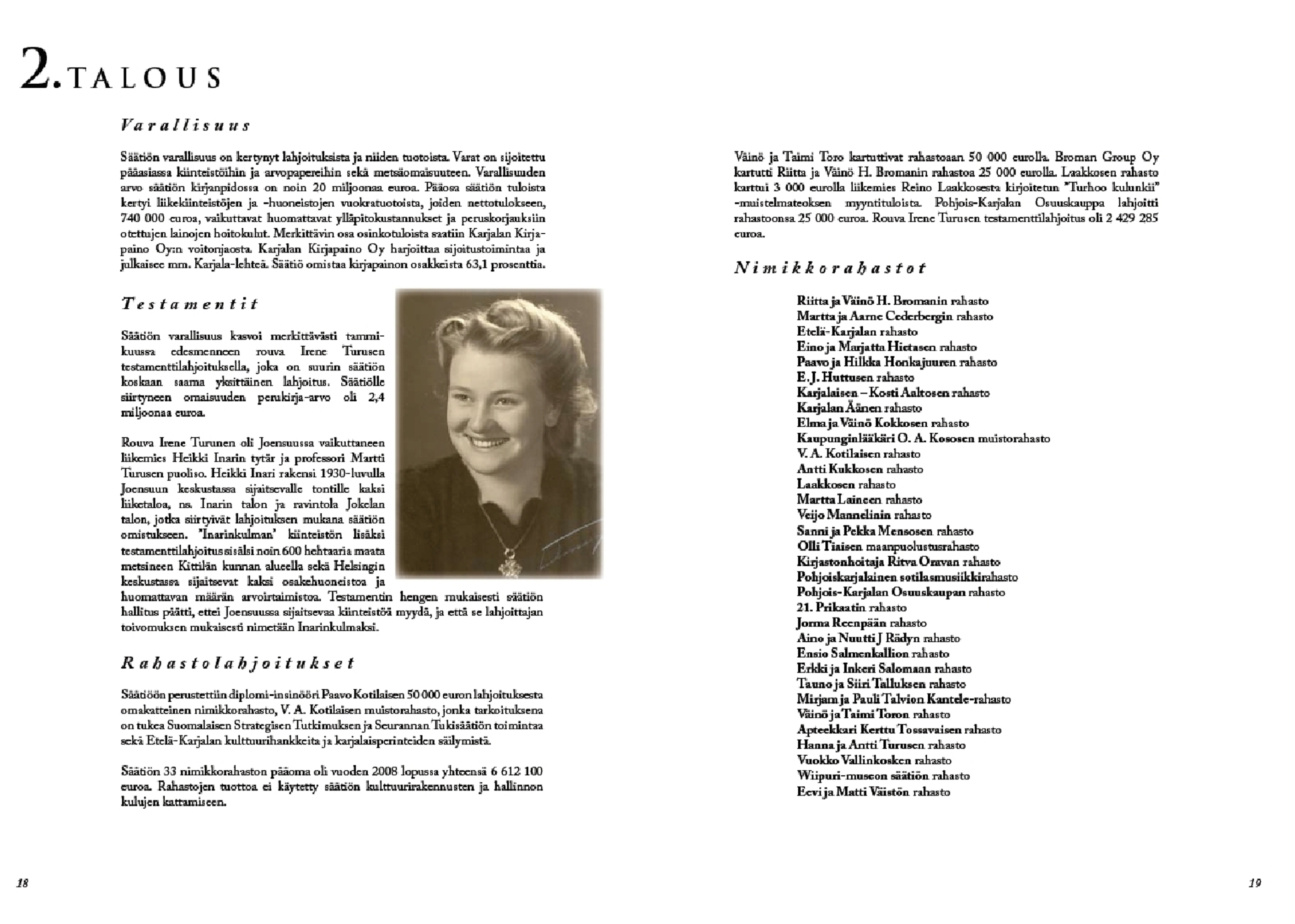

When Martti died in 1979, Irene had to run the businesses alone for the next almost 30 years. However, during her last years, due to evolving health problems, she was taken to official custody of the city of Joensuu. In her last will Irene donated the family possessions to the foundation Karjalaisen Kulttuurin Edistämissäätiö (KKES, literally ‘Foundation for promotion of Karelian culture’). When Irene died in 2008, the latest chapter in the family history took place.

The possessions of Irene Turunen the foundation received in 2008 in her last will; Screen captures from annual report of the KKES

The possessions of Irene Turunen the foundation received in 2008 in her last will; Screen captures from annual report of the KKES

Locally it was expected that the foundation would use at least part of 2,8 million euro family possessions to renovate the buildings of restaurant-hotel Jokela. However, after the investigations about the condition of the building the foundation decided to start planning a new building on the site of the restaurant-hotel-cinema complex. A complicated conflict of values arose, when the local activists didn’t accept this decision and founded the Pro Wanha Jokela Facebook-site to support the saving and restauration of the building. It is important to know, that it was also rumoured locally, that the last member of the family, Irene Turunen, had told as her inofficial last will, that the restaurant-hotel Jokela should be saved ”till the end of the world” (in Finnish metaphorically expressed as ”maailman tappiin asti”).

Seemingly due to the rumours and the complicated situation between the activists and the foundation the family history documents are still kept closed by the foundation, the legal heritor of all the family possissions. And this is where our story starts: how to study family history without standard family history documents, family archives, letters, diaries, scrapbooks or bookkeepings of the family owned businesses? Is it possible or ethically acceptable to study family history of a ”closed” family? Who owns the right for family history?

More family history: The rise and fall of Inari-Turunen families

The first member of the Inari-Turunen family, Heikki Inari, was born in a small Eastern Finland’s village Kiihtelysvaara in 19.1.1891 into a family of 9 children. Heikki was the eldest son in the family. Heikki’s original family name was Venäläinen (Finnish for: ‘Russian’), but he changed it into Inari in 1910’s or 1920’s. It is not known why he chose this family name: Inari is a large lake in Northern Finland, famous for its deepness.

Heikki Inari came to study in school in the city of Joensuu in 1902, at the age of 10. The schooling years also meant living away from the family. The distance between Kiihtelysvaara and Joensuu is approximately 30 kilometers. In those times this was too long distance to travel daily by a young schoolboy. Heikki finished also the scondary school in Joensuu, though not without some problems with the matriculation examena. From 1911 he was working at the imperial railroads, first as a young station officer in Värtsilä and later for example at the Finland’s Station in St. Petersburg.

Heikki Inari’s educational history according the school matricle;

extract from the Joensuun poikalyseon matrikkeli 1927

Somewhere during Heikki’s years at the railroad he did also meet a Russian girl Maria Pauloff (born 15.6. 1894 in St. Petersburg), who had studied in Smolna girl school. This might have happened in 1917, when Heikki was nominated as a clerk at the railway station in St. Petersburg. Heikki and Maria got married in 1920. Maria was a daughter of Ivan Pauloff, a Russian state officer. Maria was seemingly from quite different cultural order than Heikki himself. The fate of the other Pauloff family members during the revolution and the muddled years right after that are not known. In the film Raja 1918 (2007) you can get some idea of these turbulent years.

Working at the raildroads does not make you rich. Perhaps as a railway worker Heikki was able to hear rumours and conversations between travelling businessmen about possibilities to become rich by investing to land and forest. Whatever the truth, during those years Heikki must have learned how to take advantage of the new economic possibilities of the 20th century. Before moving to Joensuu Heikki had already run some kind of business in land and forestry market in 1920’s. This is also said to be the main source of capital for his investments in Joensuu city (See: Piispa & Maironiemi 2004).

Heikki and his wife had two children, son Olavi Heikki (born 20.9.1921 in Käkisalmi, on the southern shore of lake Ladoga) and girl Irene Anna Maria (born 5.6.1925). In 1934 Heikki and Maria bought a lot and a shop at the margins of the city of Joensuu where they started the Cafe-Restaurant Jokela the same year in an old building made out of logs. On the site of the shop they built in 1939 a new hotel-restaurant-cinema -complex Jokela/Kino-Karjala. The architect for this new building was Aulis Hämäläinen, who worked also for the Finnish Tourism Association, and acted as the main architect for the present Hotel Pohjanhovi in Rovaniemi. On the same lot Inaris had already in 1936 built a block-of-flat, where they lived themselves and ran a public sauna in the basement of the house.

The construction of the hotel was connected with expectations of having the Olympic games in Helsinki in 1940 (actually, due to the II WW the games were cancelled). Foreign tourists coming to Finland were also expected to travel around the country and among others visit Eastern Finnish attractions, Koli mountains, Sortavala and Valamo monastery island on the lake of Ladoga. In those times Sortavala and Valamo were part of the Finland (the trains to Joensuu from Viborg and southern Finland came via Sortavala). In this light Heikki’s investments in new hotel-restaurant were quite reasonable and a good example of his trained nose for business. Movie theater Kino-Karjala, the second cinema in Joensuu, could also be seen as a sign of seeing the importance of rising popular culture and financial potentials of new urban leisures. The public sauna could be seen as an answer to the needs of local residents of Joensuu and also the (Finnish) hotel residents of the Hotel-restaurant Jokela. The cinema was closed at the end of 1980’s and used as a bingo and a flee-market during its last years. The sauna was closed already in the beginning of 1960’s, after the death of Heikki Inari.

The tragedy of the Inari-Turunen families consists of the total extinction of the family after two generations and five family members. The son Olavi died because of war injuries already in the end of the second world war, in 19.10. 1944 at a war hospital in Varkaus. At this time he was only 22 years old. He is buried at the local graveyard in the family grave of Inari-Turunen family. In the tombstone he is entitled a secondary school graduate (Finnish: ‘ylioppilas’) and a lieutenant. A fact worth mentioning is, that he is not buried at the nearby soldiers’ honorary graveyard. It took 17 years, when the next family member, Heikki Inari himself (died 21.9.1961) was buried to the family grave.

Olavi Inari’s educational history according the school matricle;

extract from the Joensuun poikalyseon matrikkeli 1990

It is not known where and how long the daughter of Heikki and Maria Inari, Irene Turunen, went to school. In 1948 she got married to a famous choir leader Martti Turunen (born in Viipuri), a friend of her father from the choir scene. Martti was 23 years older (he was born in 11.8. 1902) than Irene. After his death (29.4.1979) he was first buried in Helsinki, where he and Irene were living at that time. Later Irene had his remnants transferred to the family grave in Joensuu.

The couple did have no children. During her husband’s choir visits abroad Irene tried to find help for the problem, but without a result. It is not known, if the husband Martti Turunen was ever suspected or studied for the same problem.

The mother Maria Pauloff was living most of her life in Joensuu. After the II WW she was often seen visiting the grave of her son at the local graveyard. When Heikki Inari died in 1961, daughter Irene Turunen took hold of the businesses together with her husband Martti Turunen. The couple had apartments both in Helsinki and in Joensuu and had to travel between the cities every now and then.

After Martti Turunen died in 1979, Irene became the sole head of the businesses. Her mother Maria Pauloff died in 12.5.1986. During her last years Irene (Irene died 20th of January in 2008) lived alone in Joensuu, mostly at the family house, a block-of-flats behind the restaurant-hotel Jokela.

Open questions

Lots of interesting questions arise because of the interesting history of the family. Many questions can’t be answered due to the missing family archives. An interesting question is also, whether there are any other ways to give answers to these questions? Other historical sources or maybe oral sources? Reminiscences of persons, who personally have met Irene or other family members?

* Was it typical for a boy from Kiihtelysvaara to go to school in Joensuu? What does this tell us about his parents social situation?

* How did Heikki gather the capital for his investments in Joensuu?

* How did Heikki and Maria meet? Did Maria know Finnish? (Heikki apparently knew Russian because of his work at the railroad)

* What was the language of communication within the family of Inari? Finnish? Russian? How much Russian culture Maria taught to her children?

* Why is Olavi not buried in war heroes’ part of the Joensuu graveyard?

* What kind of education did Irene receive? Was she planned to act as a future director of family businesses after Olavi’s death?

* What were the mutual roles of Martti and Irene Turunen regarding the family businesses after the death of Heikki Inari in 1961?

* How important or well-known the Inari-Turunen families were on the local and national level? Do newspapers mention the important birthdays (60’s, 70’s) of the family members? Are there any obituaries of the family members in local (Karjalainen, Karjalan maa) or national (Helsingin Sanomat, Uusi Suomi) newspapers?

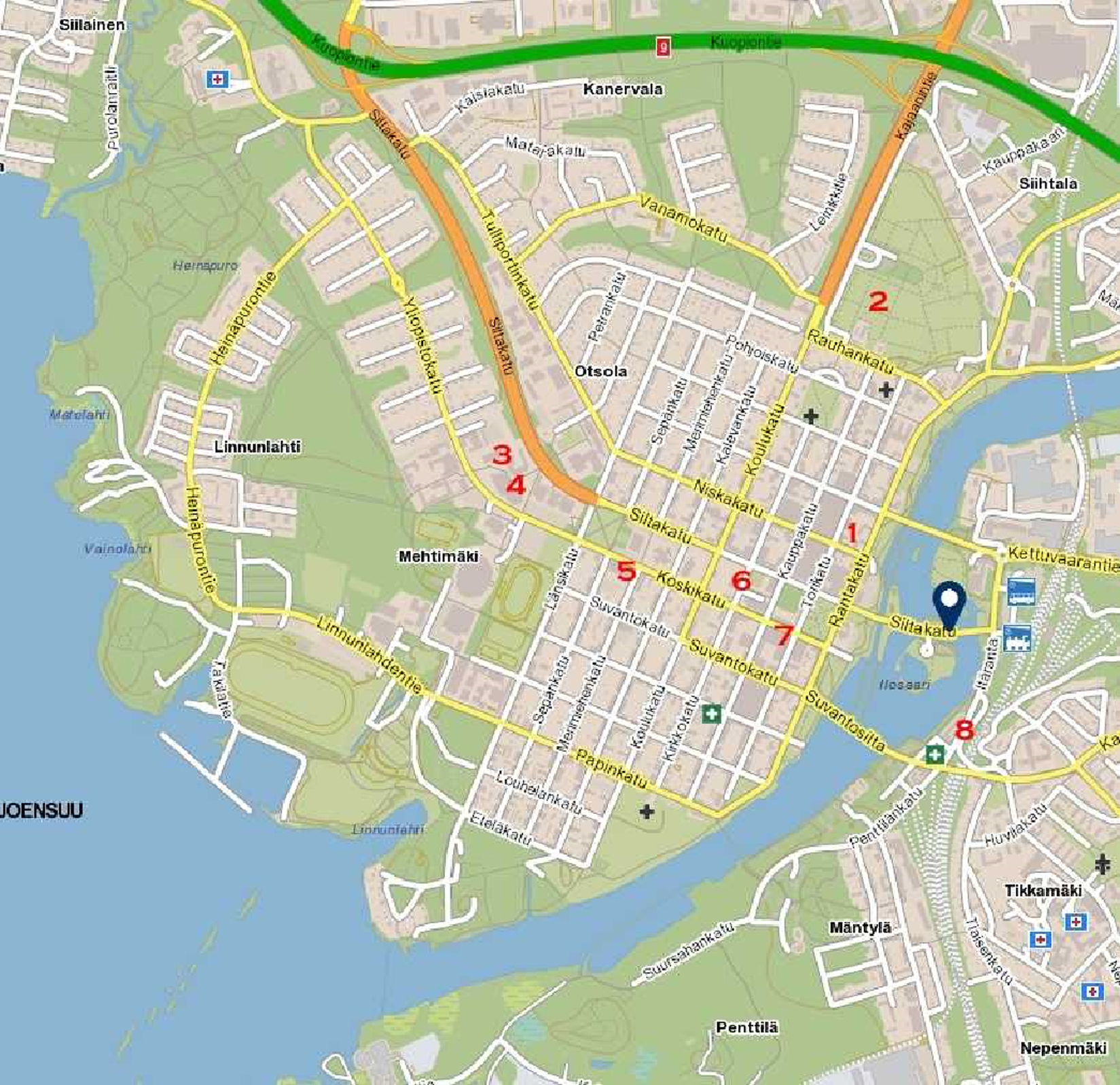

It is possible to find answers to these questions also without standard family historical sources. In the following map there are some suggestions for archives, museums and sites of memory, where you could start the search for a deeper understanding of this interesting business family.

Walking tour:

archives and sites of memory

Map of Joensuu with suggestions about places where to start

1. The building of former hotel-restaurant Jokela at the corner of Niskakatu and Torikatu

2. The family grave of Inari-Turunen families at the Joensuu graveyard

3. Finnish Literature Society’s Joensuu tradition archives at the university campus (Yliopistokatu 6). Oral history interviews with the customers of Jokela restaurant. In the same building you can also visit the provincial (historical) archives of Joensuu.

4. The university library at the university campus (Yliopistonkatu 4). Research literature about Martti Turunen’s career as a famous Finnish choir leader.

5. The main library of Joensuu (Koskikatu 25). Newspaper articles (on microfilm) from different years. Research and literature about the North Karelia.

6. The Joensuu Art Museum (Kirkkokatu 23). Former boy school of Heikki Inari and his son Olavi Inari.

7. The North Karelian Museum Carelicum (Koskikatu 5). In museum collections there are some photos and items from the family of Inari-Turunen received before the beginning of the conflict.

8. City archives of Joensuu (Penttilänkatu 7-9)

The family grave at the graveyard in Joensuu; Photo: Jyrki Pöysä

The house of the Provincial Archives of Joensuu at the university campus; Photo: Jyrki Pöysä

The Joensuu Art Museum; Photo: Jyrki Pöysä

FURTHER READING:

Facebook: Ravintola Wanha Jokela (https://fi-fi.facebook.com/pages/Ravintola-Wanha-Jokela/214809975205686)

Häyrynen, Antti (2008): Sinivalkoiset äänet. Ylioppilaskunnan laulajat 1883-2008. Helsinki: Otava.

Javanainen, Riikka (2013): Suojella vai ei? Rakennussuojelun päätöksenteko. Hotelli-ravintola Wanhan Jokelan ja Jyväskylän Shellin huoltoaseman suojelupäätökset. Pro gradu -tutkielma, Jyväskylän yliopisto, museologia.

Kaarlenkaski, Taija & Kupiainen, Karoliina & Pankamo, Heidi & Pyykkönen,

Pirita & Pöysä, Jyrki (eds.) (2005): Joensuun paikat. Joensuu: Suomen kansantietouden tutkijain seura.

Makkonen, Elina (2004): Muistin mukaan. Joensuun yliopiston suullinen historia. Joensuu: Joensuun yliopisto.

Marvia, Einari (ed.) (1966): Suomen säveltäjiä, II. Porvoo: WSOY.

Piispa, Jyrki & Maironiemi, Eino (2002): Wanha Jokela. Joensuu: Ilias.

Pulkkinen, Maire (ed.) (1958): Suomalaisia musiikin taitajia. Esittävien säveltaiteilijoiden elämäkertoja. Helsinki: Oy Fazerin Musiikkikauppa.

Rautio, Tommi (director) (2014): Oothan vielä. A documentary film about Jokela

Oral sources

Interviews with Anita Latola

Pedagogical relevance

The internet pages are aimed for two groups of young people:

* School-children: learning about the history of their their native town Joensuu, especially about the local business history. Pages could also be seen as part of the larger project Joensuun paikat (‘My places in Joensuu’; see: Makkonen 2004). A possibility for learning about the local cityscape and the local museums and archives. The graveyard as an archive of the history of local families. Suited also for the Joensuu international sccondary school because of the language (English).

* Students at the university (history, ethnology, folklore, geography, sociology etc): Learning about how to go deeper in the history of a new residence with the help of research, libraries, archives and the practice of doing oral history with the help of interviewing. Possibility to learn about the ethical and legal questions around family history: to whom belongs family history? Who owns the rights to family history, if the family has extincted? An interesting case in cultural heritage and the legal ownership of family history. Suited also for foreign students because of the language (English).