by Anni Reuter.

Pietari Jääskeläinen (born 1879) was exiled to Siberia in an Easter night 1931 with his family. His crime was cultivating a relatively prosperous farm in Ingria, Keltto, only 20 kilometers from Leningrad. The family was labeled as kulaks, rich peasants, as “elimination of the kulaks as a class” was organized in Soviet Union.

He belonged to the Finnish minority, which also caused problems. Ingrian-Finns were Lutherans in the atheist country and spoke Finnish, not Russian. In the Soviet Union of the 1930s anything Finnish or religious became dangerous.

Pietari (age 51), his large family that included 12 members and many other families from Ingrian Keltto were deported in the cattle wagons into the unknown. This railway trip took ten days. There were over 40 persons in one wagon with their luggage, without any proper sanitary possibilities. They were given only three times food, but luckily they had some food with them.

In these inhuman conditions, they journeyed to Krasnojarsk in Siberia as they later discovered. Pietari wrote home in the 13th of May, 1931:

Greetings from the Hell of Krasnojarks!

I write to you about our life here, about children’s destiny. Children are like sentenced to death. Those ten days we had to spend in the cattle wagons were too much for their health. We got food three times, but not the children, although they had promised us…

In this barrack there are 635 persons in one department… It is difficult to describe what I see and hear, but most difficult of all, what I feel. The floors, barrack beds, every corner and inch is crowded with people sleeping, and I can hear weeping, that is breaking my heart. Near to me, side by side, are two sick children sleeping and next to me rests a mother, who is so weak that she can hardly open her mouth, her five sick children near to her. The oldest daughter trying to take care of them. Their father has been sent to work somewhere.

Here is also two bodies looking like angels, one mother smiling. Over there you can see a woman who is crying again even if her teardrops dried out, but now again falling, because the death took away her three children in one night. Over there I would not like to turn your sight but there you can see six children sleeping like lambs in their stall. From them the death, like a wolf, has taken away their mother. In the middle of the night everybody wakes up to a terrible cry, when a child is calling after her dead mother. Mother! Mother! Mother!

The youngest member of the Pietari’s family, grandson Sulo, who was not even one year, died soon. Uncle Multiainen, who was already 74 years old, tried to escape, but he was captured and beaten up so badly, that it caused his death.

Death in the beginning of the exile was typical destiny for the young and the old, because they were easy targets for illnesses and were given hardly any food – only those who worked got decent proportions.

From Krasnojarsk the rest of the family moved to other exile destinations, to the town of Yeniseisk and later to a small village on the other side of the Yenisei River, which was badly struck by a famine.

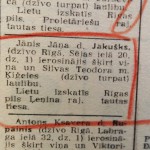

After they survived the famine, family was ordered to move to a goldmine and forest area near the Stony Tunguska River. They started to work in the forestry and goldmine, cultivating the land in their free time. Youngest sisters Elsa, Helena and Susanna could go to school. At the same time their relatives were deported from Ingria to Central-Asia and Kola-Peninsula, where the conditions were very harsh.

In 1938 Pietari and his three sons Matti, Pekka and Simo were imprisoned from the exile. Only the youngest sons came back, but Pietari and his oldest son Simo died in a prison. Exile resembled prison in many ways – you were not free to move for example.

“It was like a home, but at the same time like a prison. Men were imprisoned from a prison. Only women and children were left,” told Eeva (age 22), Pietari´s daughter in her interview in 1972.

During his stay in the Siberian exile; Pietari wrote a lot: letters, diary and poems. By reading them, it is possible to get a vivid picture of life in Siberian exile, but also a view to ethnic, social and religious conditions and purges and how it felt to be far from home, often in a hostile environment. He wrote about early deaths in exile, sickness, hunger, hard work and repression, but also importance of the family, joy of life, holiday greetings and poems of history and longing.

In the letters and in the Siberian diary you find themes like hunger – food, purges – destinies of people, moving – housing and religion.

The History of Ingria and the Family Culminating in the Years of Stalin’s Terror

Finns have lived in Ingria, around Saint Petersburgh since the 17th century. The Finnish speaking and Lutheran minority in Russia had a rich cultural heritage, including oral folklore and poetry, now partly documented in the Kalevala, the Finnish national epic and the Kanteletar, a collection of Finnish folk poetry.

In the beginning of the 1600th century, a man called Simo, moved from the municipality of Jääski in Finland to Ingria, and he was given the name Jääskeläinen according to the place of his origin. He and his family members were peasants as most of the Finns back in those days. They were free peasants, but after Russian empire had occupied Ingria from Sweden, they became serfs, one kind of slaves.

In Russia, serfdom in its extreme form lasted until 1861. After that they became free peasants again until the collectivization of the land started in the end of the 1920s in the Soviet Union. In 1930 they lost their land for good. The collectivization and dekulakization policy made little economic sense in that it led to the removal of the most efficient farmers. A man-made famine was followed by it in 1932–1933.

Because of their ethnic background as Finns and social background as peasants, Ingrian Finns living in the Soviet Union became targets of Stalin’s repressions. Deportations, imprisonments, disappearances and executions of Finns fall especially between the years 1928–1938. Many was evacuated from Ingria during the Second World War. There was 140 000 Finns living in the historical Ingria in the beginning of 1900th century. In 1940s the number of Finns had collapsed to 6000 persons.

Majority of the extended family Jääskeläinen was deported to Siberia, Asia and Kola Peninsula. Contacts between Finland and the Soviet Union collapsed and became risky. Majority of male relatives were imprisoned later because of political reasons – they were labelled as counter-revolutionary.

It is estimated that 32–40 million people died in Stalin’s purges altogether before the end of the World War II. Today we call purges as ethnic cleansing and genocide.

Many family members escaped from the exile, some even from the Soviet Union to Finland and Sweden. It started to be possible to “return” legally 1949 or after Stalin’s death from the exile. But it was impossible for them to move to Ingria and this is why the family members moved instead to Karelia and Estonia.

The Ingrians’ national awakening towards the end of 1980s and their remigration to Finland began in the 1990s. Today both the extended family Jääskeläinen and Ingrian Finns in general lives in diaspora.

How the Family Archive Came to Being?

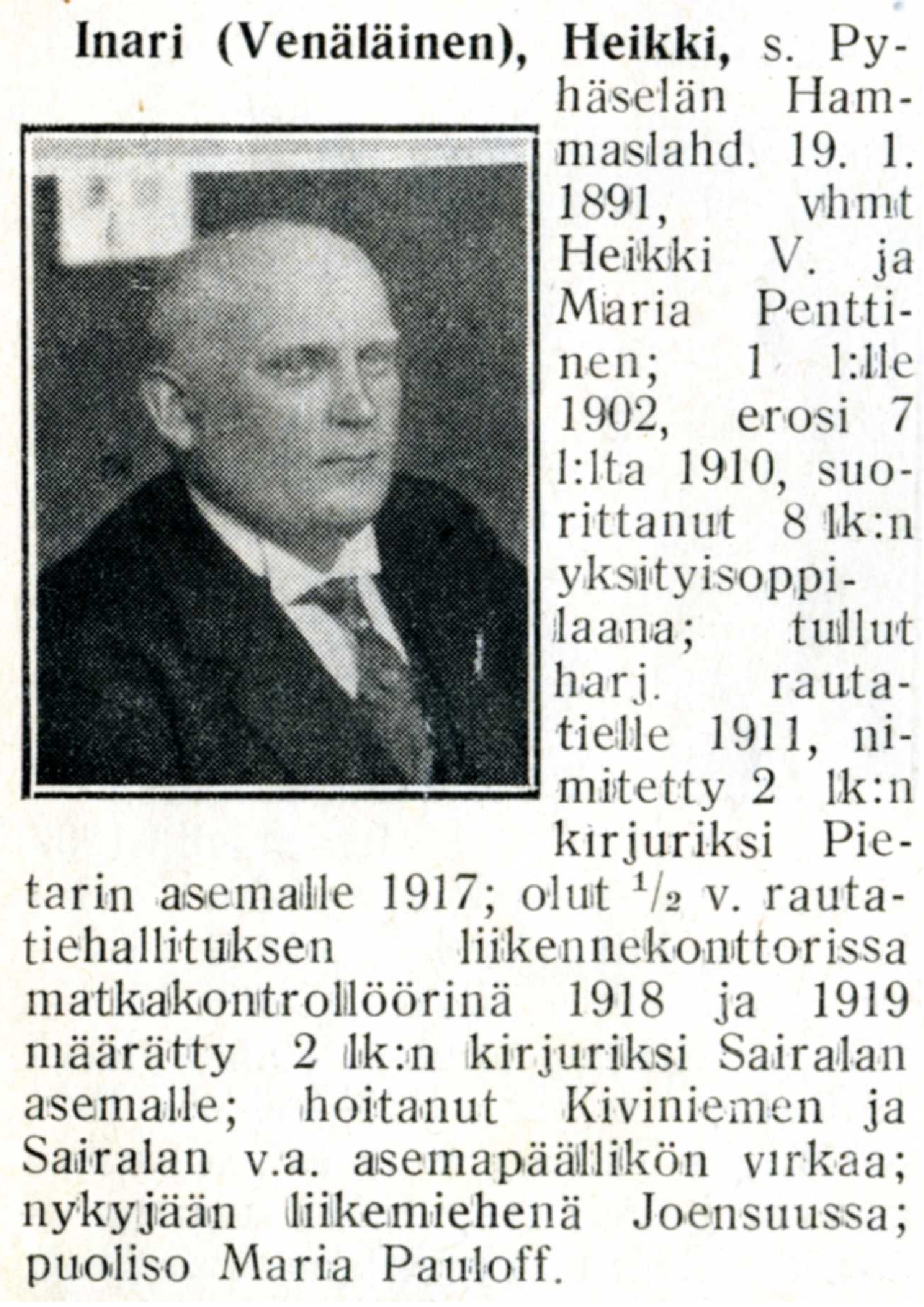

Pietari’s son Juhani Jääskeläinen (born 1907) came to Finland from Ingria in 1925. He wanted to study in Finnish in a high school and later religion at the university, which were both impossible in the Soviet Union. He got a refugee status in Finland and later he started his studies at the university.

He received letters from home. Letters that told about the life of his peasant family in a communist country: collectivization, lack of food caused by it, confiscation of their land and property and repression against Lutherans and peasants labelled as kulaks.

Soon after having started to study in the upper secondary school of Käkisalmi, Juhani got a shocking letter from his uncle in 1931. His family was deported to Siberia. There was not any address to write them anymore nor any knowledge what was going to happen to them.

This piece of news were followed by letters about relatives’ early deaths in exile, sickness, hunger and terror, but also poems, photos, cards and best wishes.

“Dear cousin, I wish You Merry Christmas, but I have to shout: Are Finnish people going to die in Siberia, in Taiga, in Alma-Ata and behind Moscow, in the station of Jassakova!!! The destiny of a political prisoner has become terribly miserable. I send you here some letters, valued in the free conditions you are living.” 26. March 1932, an unknown writer

Already in the 1930s, Juhani started to gather a family archive and other research material on Ingrian Finns quite systematically. He even did interviews from 1967 onwards. Juhani took part in the civic movements in Finland that were against repressions in the Soviet Union, although he was afraid of the secret police and his own deportation back to the Soviet Union. He became a Finnish citizen and a priest.

After a long time, in the 1960s and 1970s, Juhani met his sisters who had been exiled to Siberia. They had been children when they got separated and they were already retired from their jobs when they met after the exile years. Almost 50 years had passed. Juhani Jääskeläinen was one of the first ones to write about the purges of Finns in the Soviet Union.

Today the family archive includes letters (from 1927), Pietari’s diary from Siberian exile, others diaries and notes, poems, interviews (from1967), photos, family trees and newspaper clips. The archive is today preserved primary by the family members. Because the extended family lives today in diaspora in Finland, Russia, Sweden and Estonia, are there archives in every country.

Pedagogical Potential of Ingrian Finnish Family History

Finns in Finland and Russians living in historical Ingria know little or nothing about Ingrian Finnish history. Through Ingrian Finnish family histories the history of Ingria could be made more visible.

History of Ingrians has been absent from history and school books in Finland. Family archives and oral histories maintain this forgotten history. Family histories and archives have a personal, historical and cultural value and could be studied at the university level.

Family history could be used also in education in order to add knowledge of Stalin’s terror and understanding the consequences of it in more personal level. Archival materials make it possible to approach history and culture as continuative life history experienced by real people, not as “national history”.

Researching family history is one way to understand for example how the history of one generation affect also the following generations. The Ingrian Finnish family history could be used as an example of researching the own family.

UNIVERSITY LEVEL

Possible questions could be: How to reach and to interpret archival materials? What the historical context means? How do the people remember, privately or publicly, individually or collectively?

Example 1. Oral history / Sound recordings

Jääskeläinen’s family archive contains sound recordings, oral history and life stories from 1967. Some of them are interviews, some of them are recordings of family meetings. It is needless to say, that these make differing contexts for narration. How do they differ? What do they tell? How do they tell stories, individually or collectively? Do the family members use “I” or “we”? Whose voice do you reach?

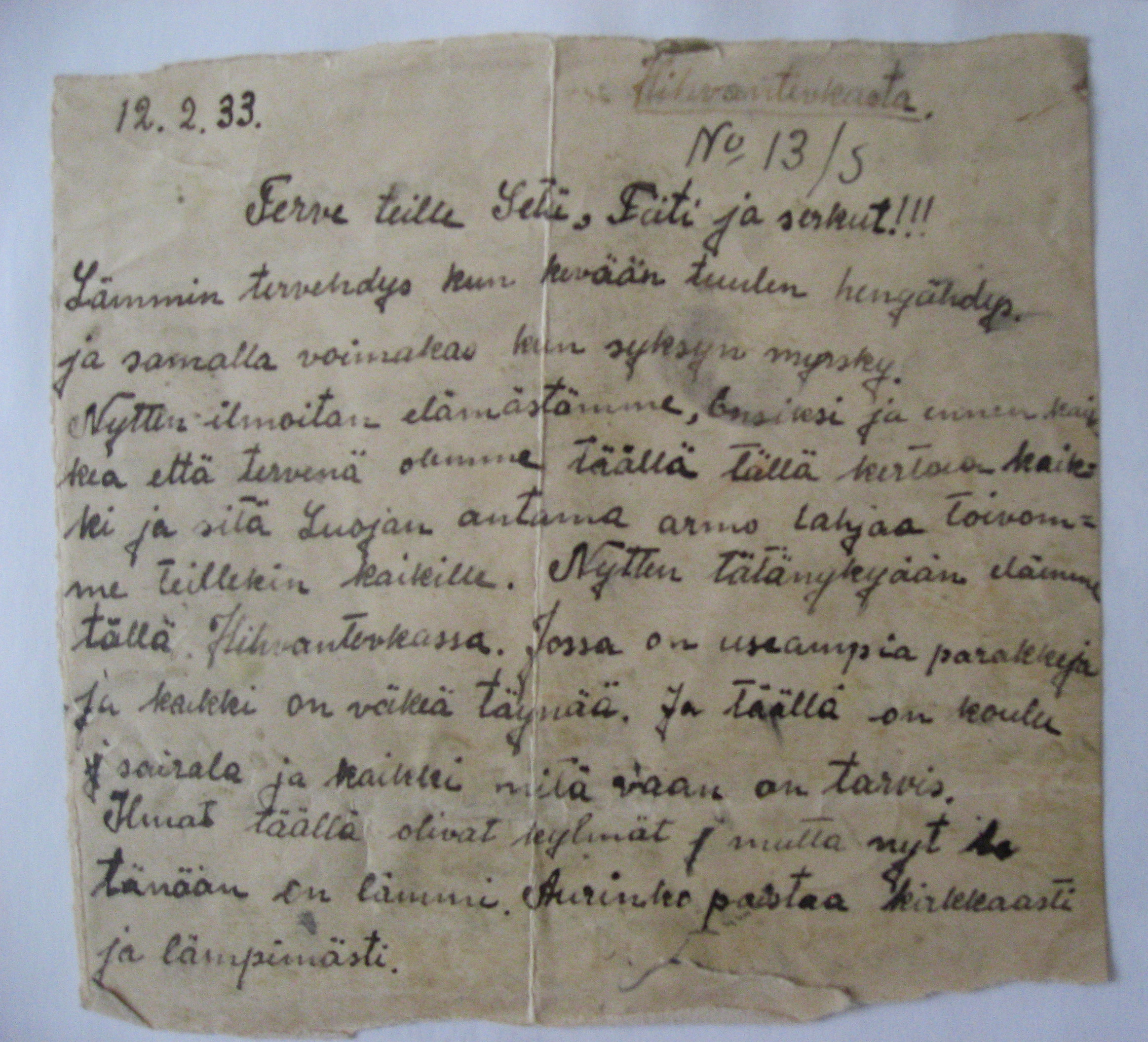

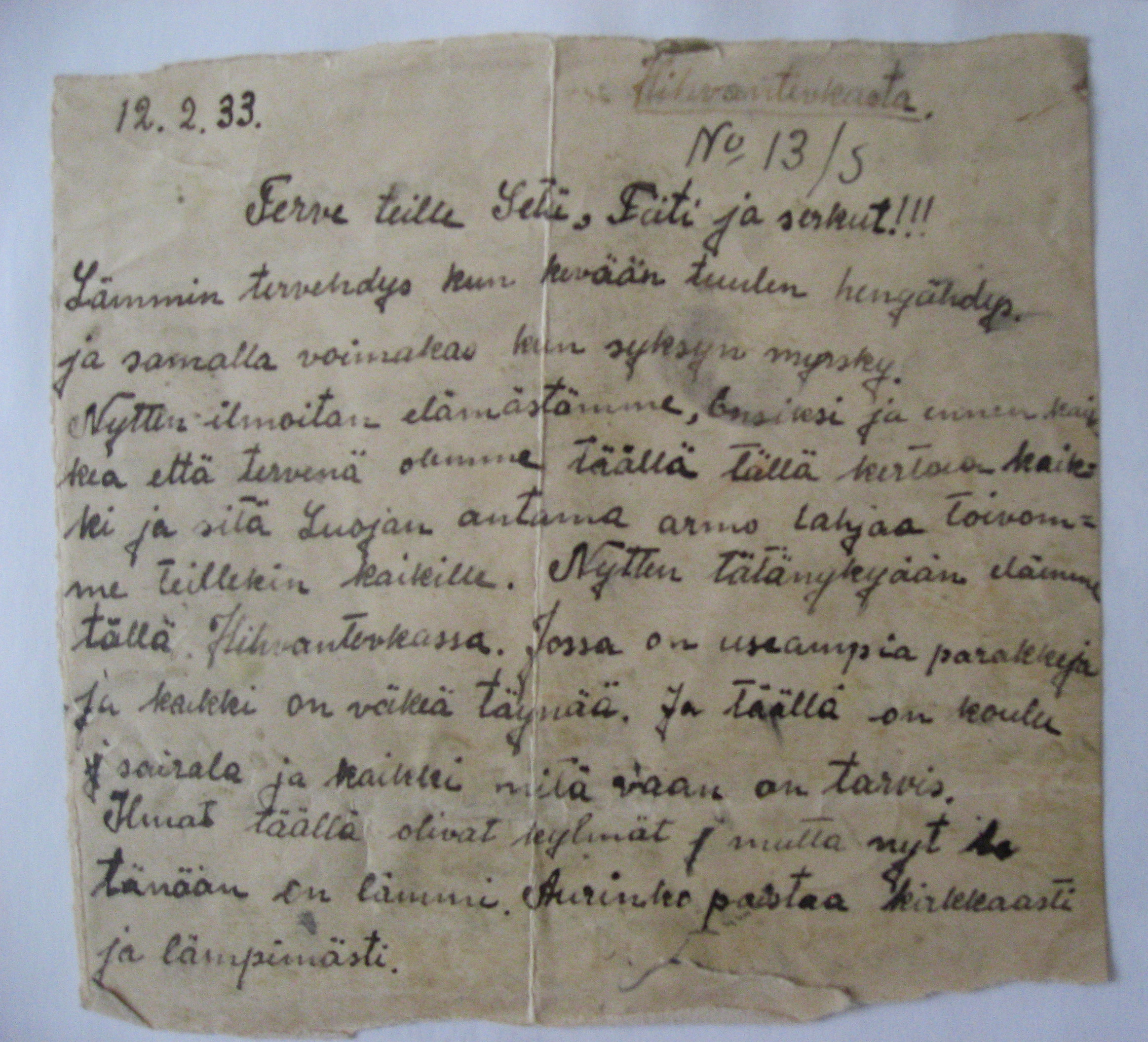

Example 2. Letters and diary

What and how did the family members write? What words were used and why? Can we interpret the letters with the information we have? What information is/can be lost from our perspective?

How does letters and diary communicate? What happens when one genre changes into another? How to interpret?

Example 4. Gaps and silences

Were there things that nobody wrote or talked about? What is missing from the archival material? Why? What was too sensitive, horrific or dangerous to be written down? Are there classical or biblical myths and narrative formulas in the archival material? How do they affect interpretation?

In discussions it is possible to ask: Who writes history? Who owns history? How is history created or invented? How to write history?

Published histories are always interpretations and they need to be complemented, contradicted and re-written. From whose perspective is history created?

HIGH SCHOOL LEVEL

Pietari’s and his brothers Anttis’ life stories have been used in Finnish high school history education. You can find their family and life stories in Edu.fi – Education portal for teachers in Finland. Wider use would need publication of diary, interviews and letters.

Pietari’s and his family’s deportation >> LINK HERE

Antti’s and his family’s destiny in Soviet Union >> LINK HERE

Holocaust Memorial Day, in Finnish Vainojen uhrien muistopäivä, Memorial Day of Purges is celebrated on the 27th of January. Celebration of the day underlines the value of human rights and the right to remember. The Holocaust Day in Finland could contribute to the theme of Finnish victims of wars, purges and genocides.

Some questions that could be used:

- What were the differences between Hitler’s and Stalin’s terror? Where there something in common?

- Which were the consequences of deportations and terror for the individual, the family and the group she or he belongs to?

ADULT EDUCATION

How to create a family archive? Why to create a family archive? (See separate document.)

- How to use public archives? How and where to donate a family archive?

- How to write a family history?

- How archival materials could be used as background material for creative or biographical writing?

ALL LEVELS

- How to research your own family? How to make an interview and collect other material for family history?

- What ethical aspects should be taken care of in collecting and using archival materials? See for example Oral History Society UK http://www.ohs.org.uk/ethics.php UK data Archive http://www.data-archive.ac.uk/create-manage/consent-ethics

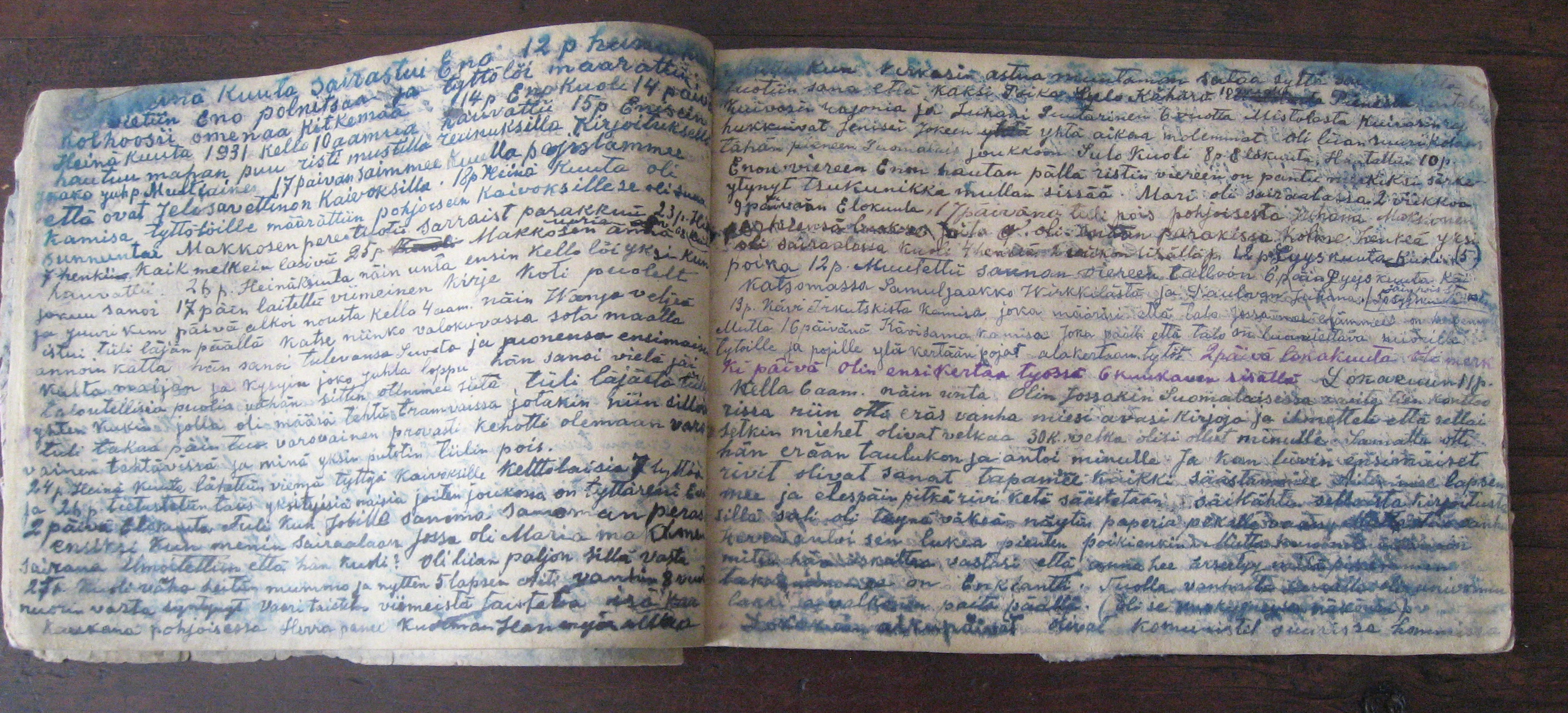

- Materiality of archival sources? Materiality is an important attribute of archival material. For example Pietari Jääskeläinen’s diary is an impressive artifact. How it felt to write a diary in the exile, how was it to carry that diary, hide it from the secret police GPU and to worry about losing it? Even if the content of the diary was digitized, aspects of materiality would not be easily transmitted online.

PICTURES

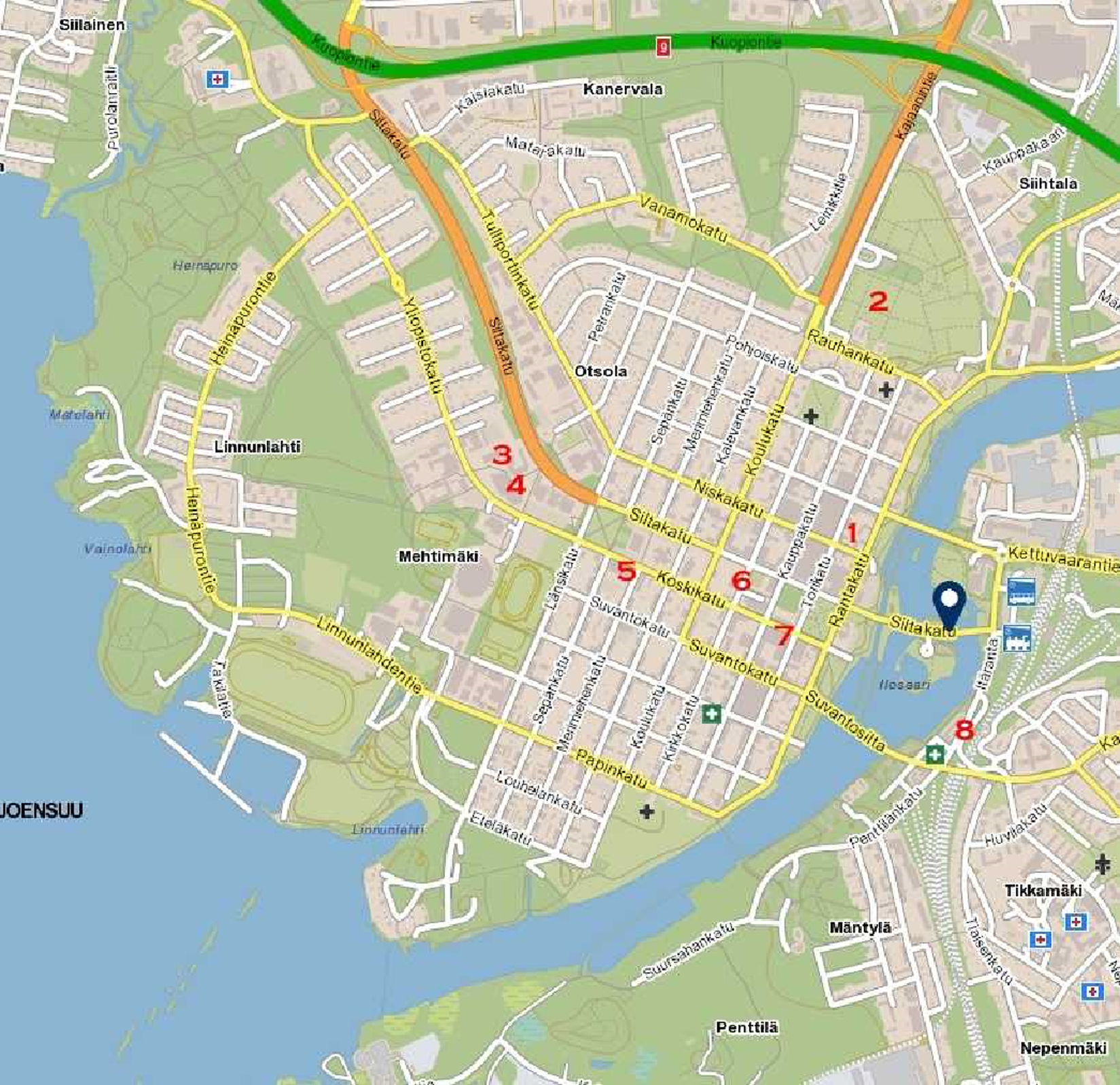

The exile destinations of Jääskeläinen family in 1930s: from Ingria to Kola-Peninsula, Central-Asia and Siberia.

Family Jääskeläinen in Keltto, near Leningrad 1921, before terror.

Sisters in Siberia 1931

A letter from Siberia, 1933

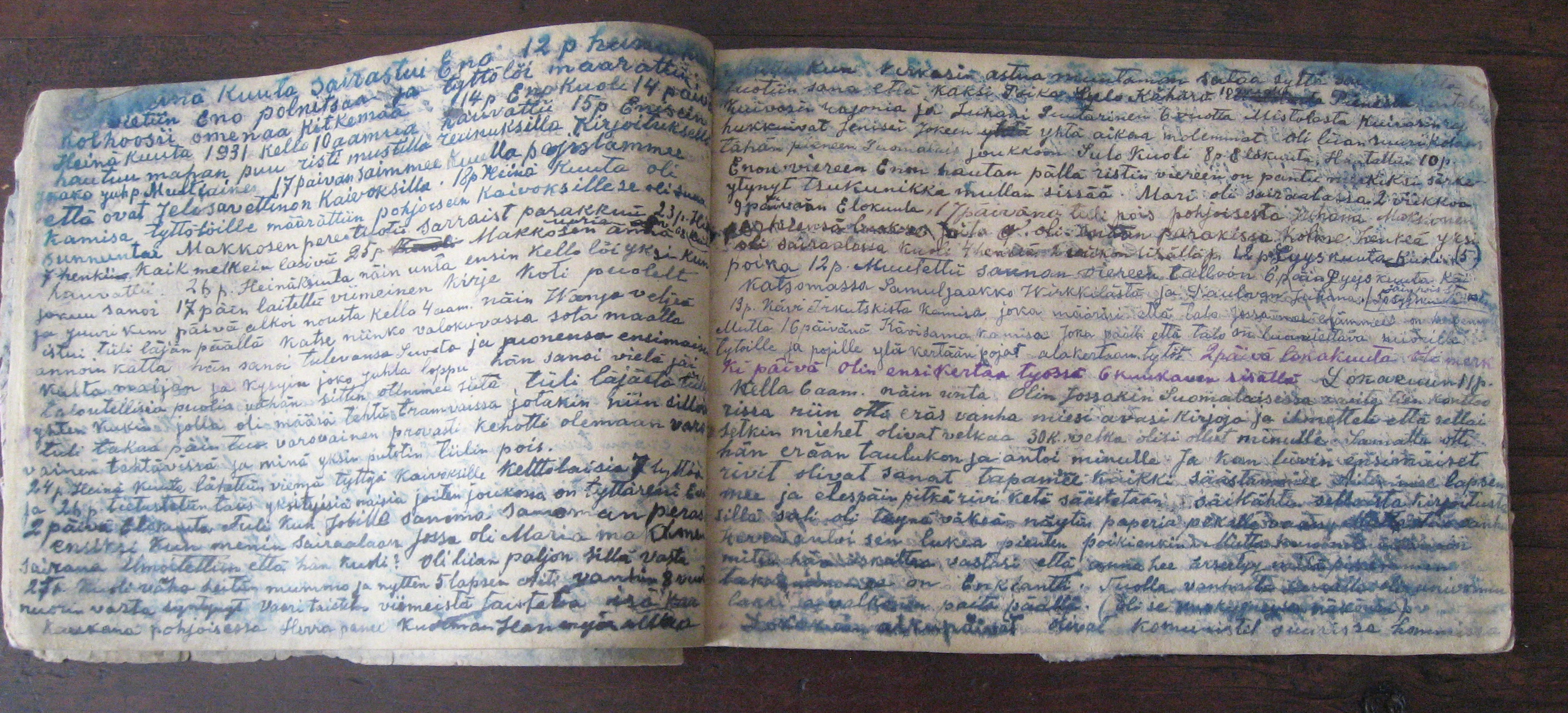

Pietari’s diary from Siberia (1931-1937)

FURTHER READING:

Applebaum, Anne: Gulag. A history of the Soviet Camps. Penguin Books, 2003.

Litvinenko Olga & Riordan James: Memories of the dispossessed. Descendants of Kulak Families Tell their Stories. Bramcote Press, 1998.

Peltonen, Ulla-Maija: Memories and Silences: On the Narrative of an Ingrian Gulag Survivor. In: Memories in Mass Repression. Ed. Adler Nanci et al. Transaction Publishers 2009.

Inkeri. Historia, kansa, kulttuuri. Toim. Nevalainen, Pekka & Sihvo, Hannes. Suomalainen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1992.

Sihvo, Jouko: Inkerin kansa 60 kohtalon vuotta. Tammi 2000.

www.inkeriliitto.fi (Ingrian Society in Finland)

www.inkeri.com (Ingrian Culture Society)