by Mâra Zirnîte.

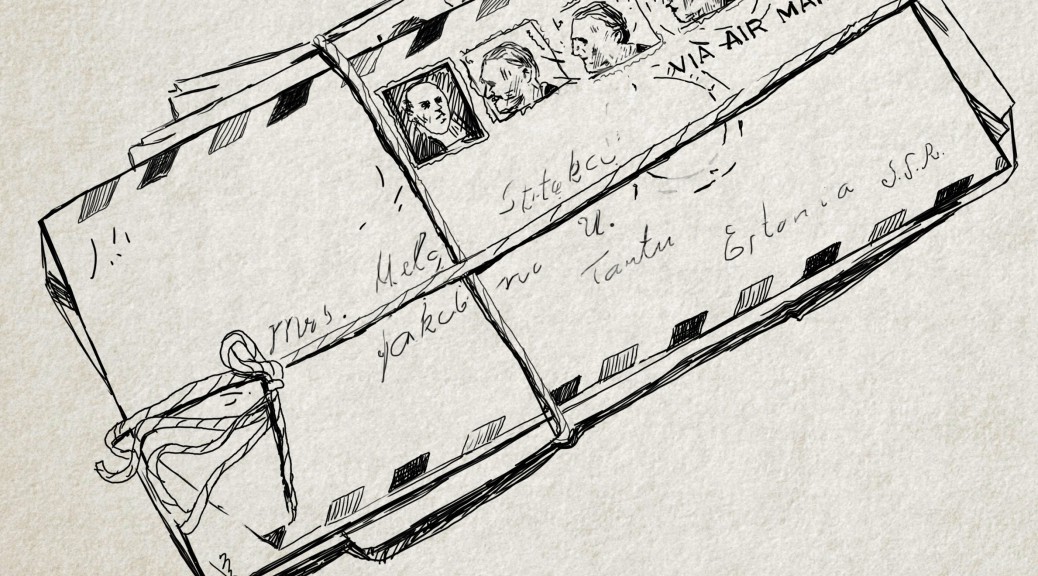

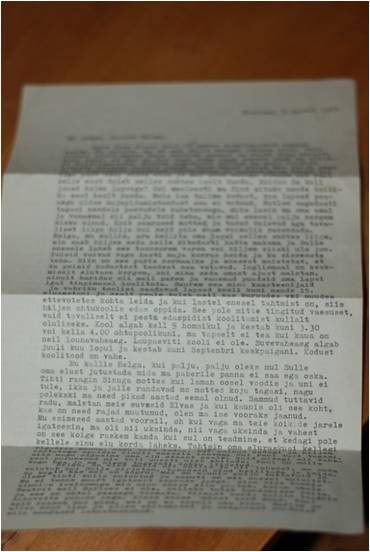

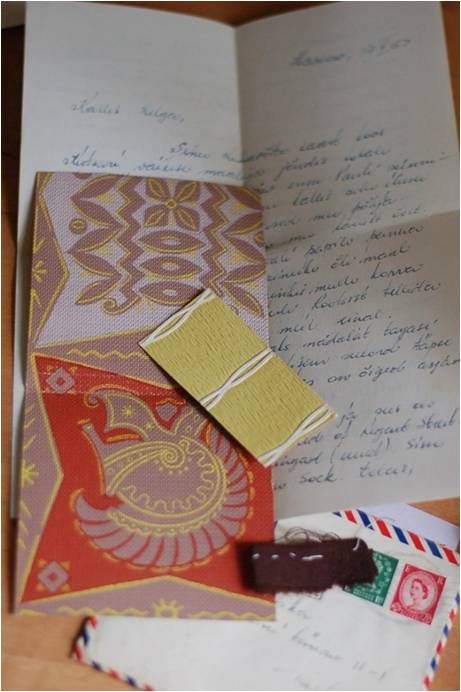

The life history of Lilija Šica, selected for family portrayal and multimedia presentation, consists of several sources: oral history records, written memories, family photos and epistolary archives, photos of Lilija’s self made textiles and a video clip. The Latvian National OH archive includes over 4000 audio interviews – the sources for qualitative research and topical publications about individual life experiences.The life histories’ records are the main form of sources, initiated by the OH researchers at the Institute of Philosophy and Sociology, University of Latvia. [Interviews provide sources on various research topics such as cultural identity, the role of traditions and impact of regional culture, political and social changes, gender roles, etc. Family history and transmissions of cultural traditions and values, communication between generations and family members are also among the topics.] Selection of narrators depends on the research objective – during systematic field-work for obtaining life experiences of the Latvian people within and outside of Latvia.

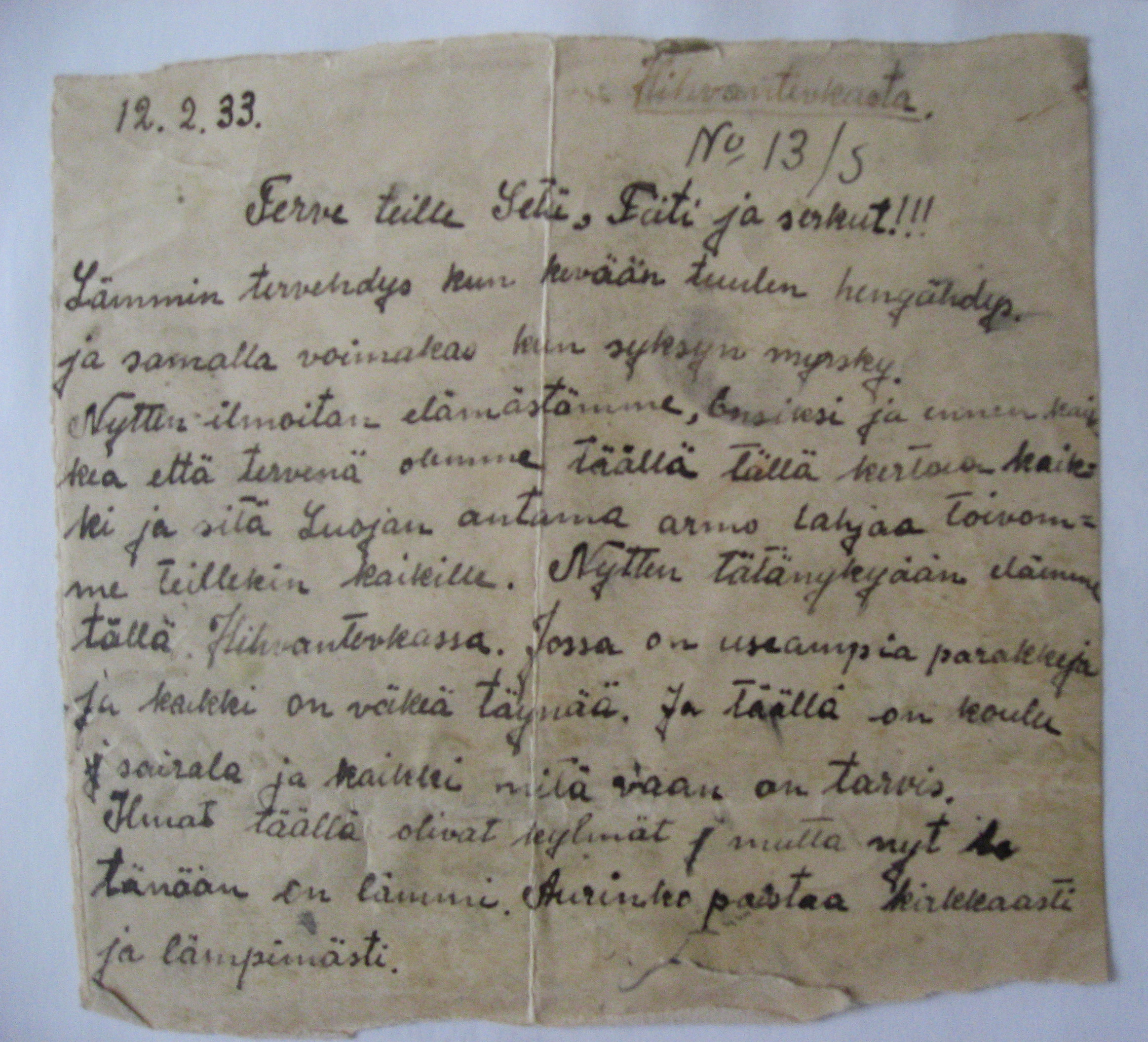

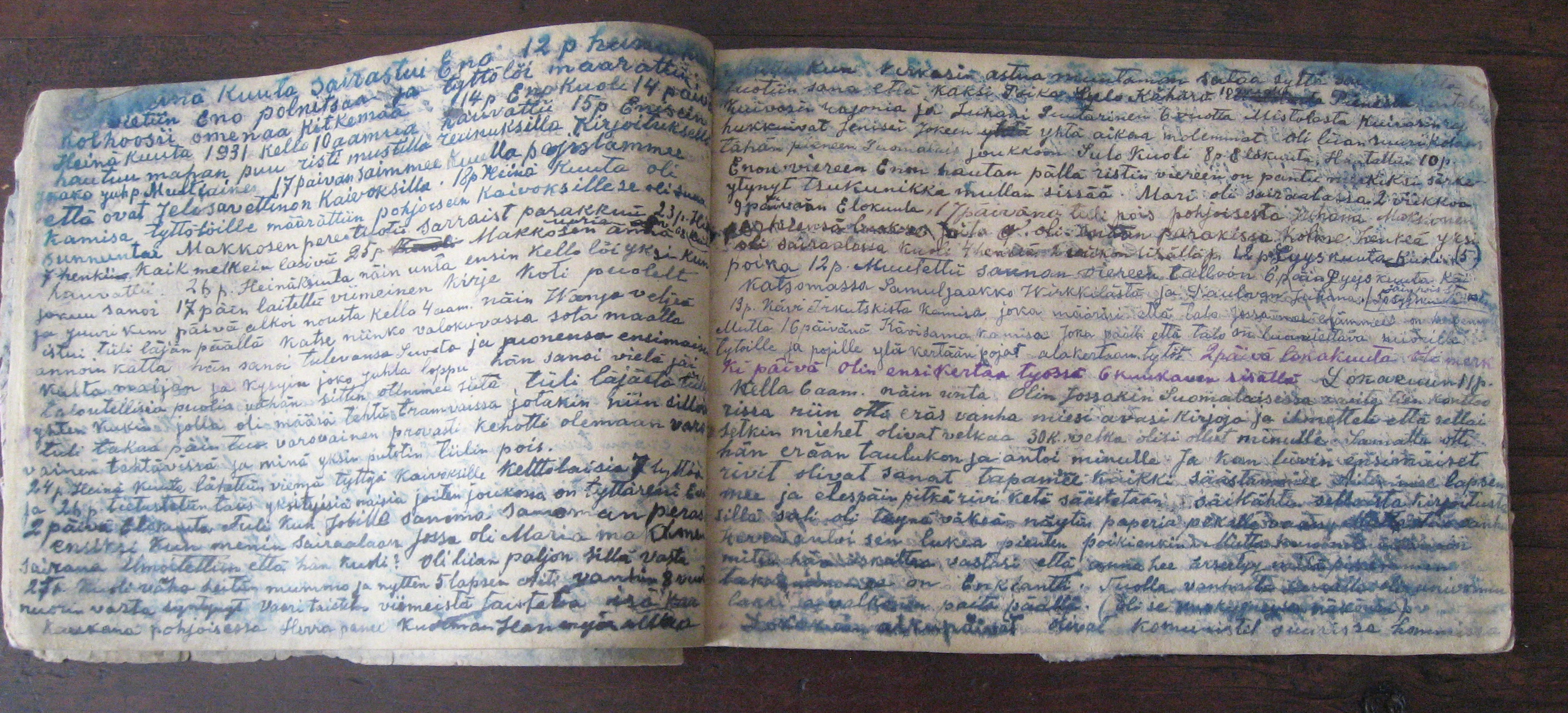

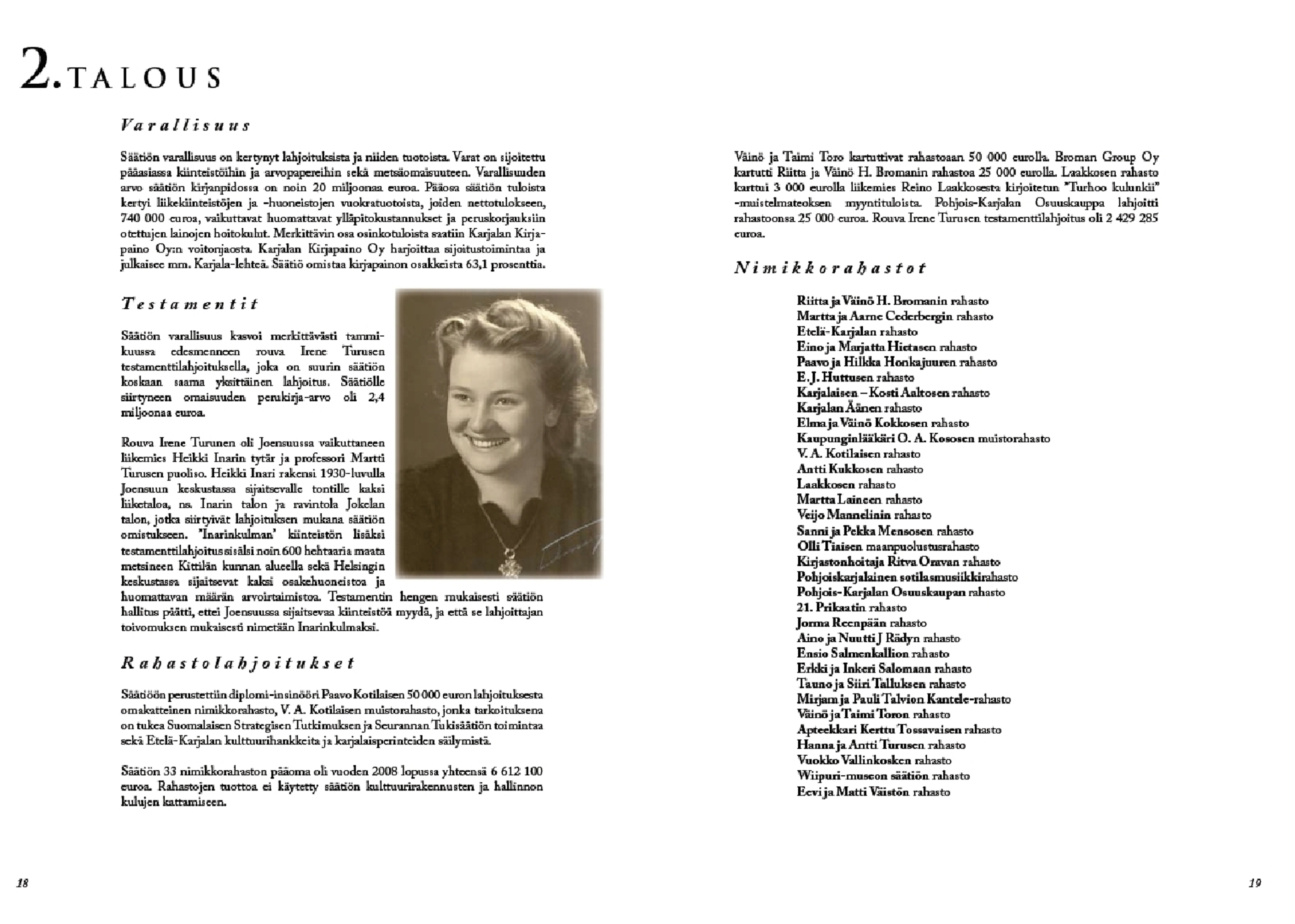

Recommendation to introduce Lilija’s life story we received at her birth place. Her roots there were alive and she continues active communication with local people. The local history explorer knows her very well, although Lilija has lived there at least one third of her life. Lilija has given birth to six children, and the number of her descendants is growing. Lilija has followed her mothers’ practice and has written memories of childhood and early youthhood. The OH interviews with Lilija were recorded in 2010-2012, after Lilija’s 90th birthday. She still has a retentive memory.

The three years of cooperation between the researcher and Lilija resulted in Lilija’s own book of memories and a multimedia presentation made by the researchers. (We present the part of that materilal.)

Cultural and historical context of the resource

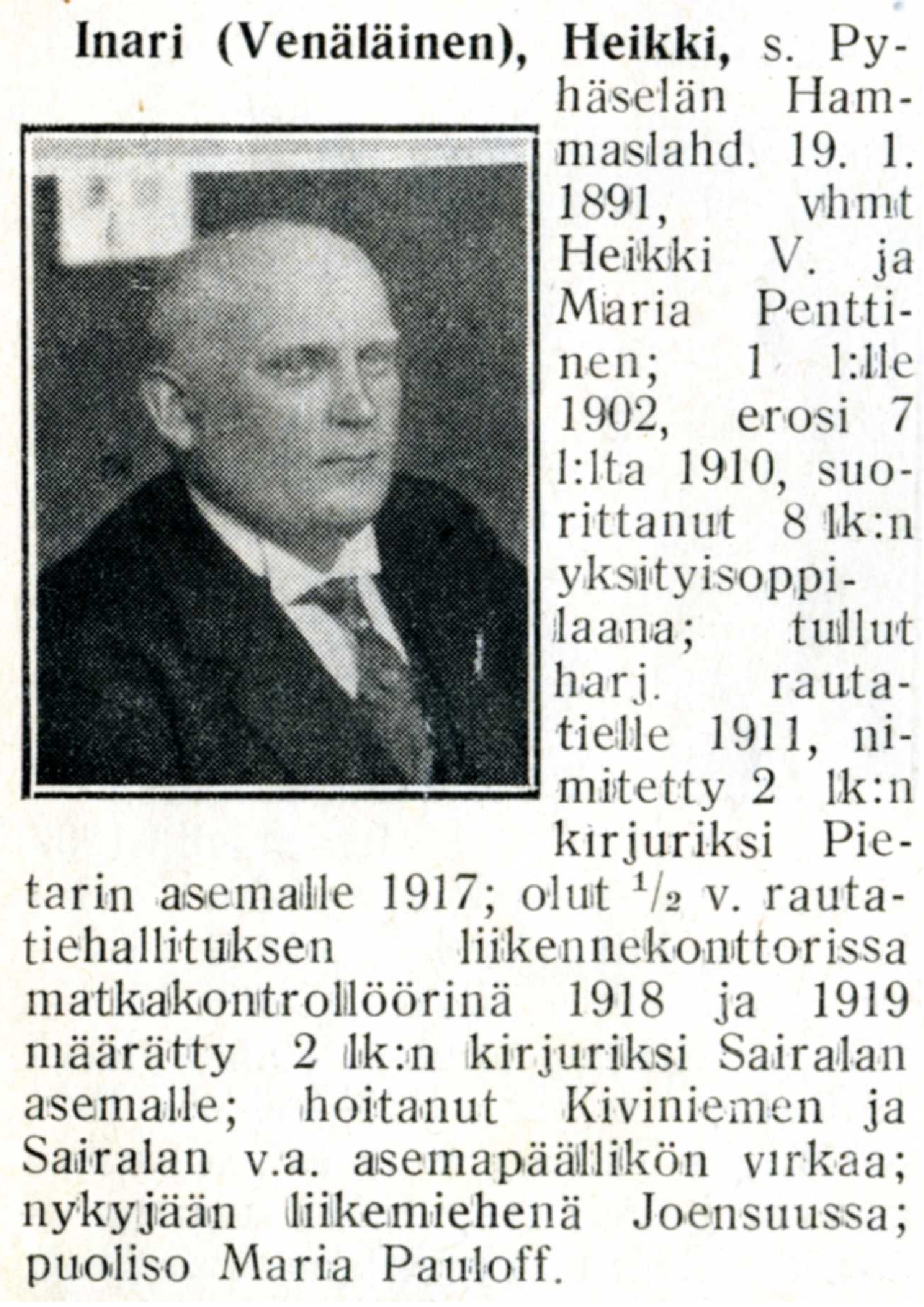

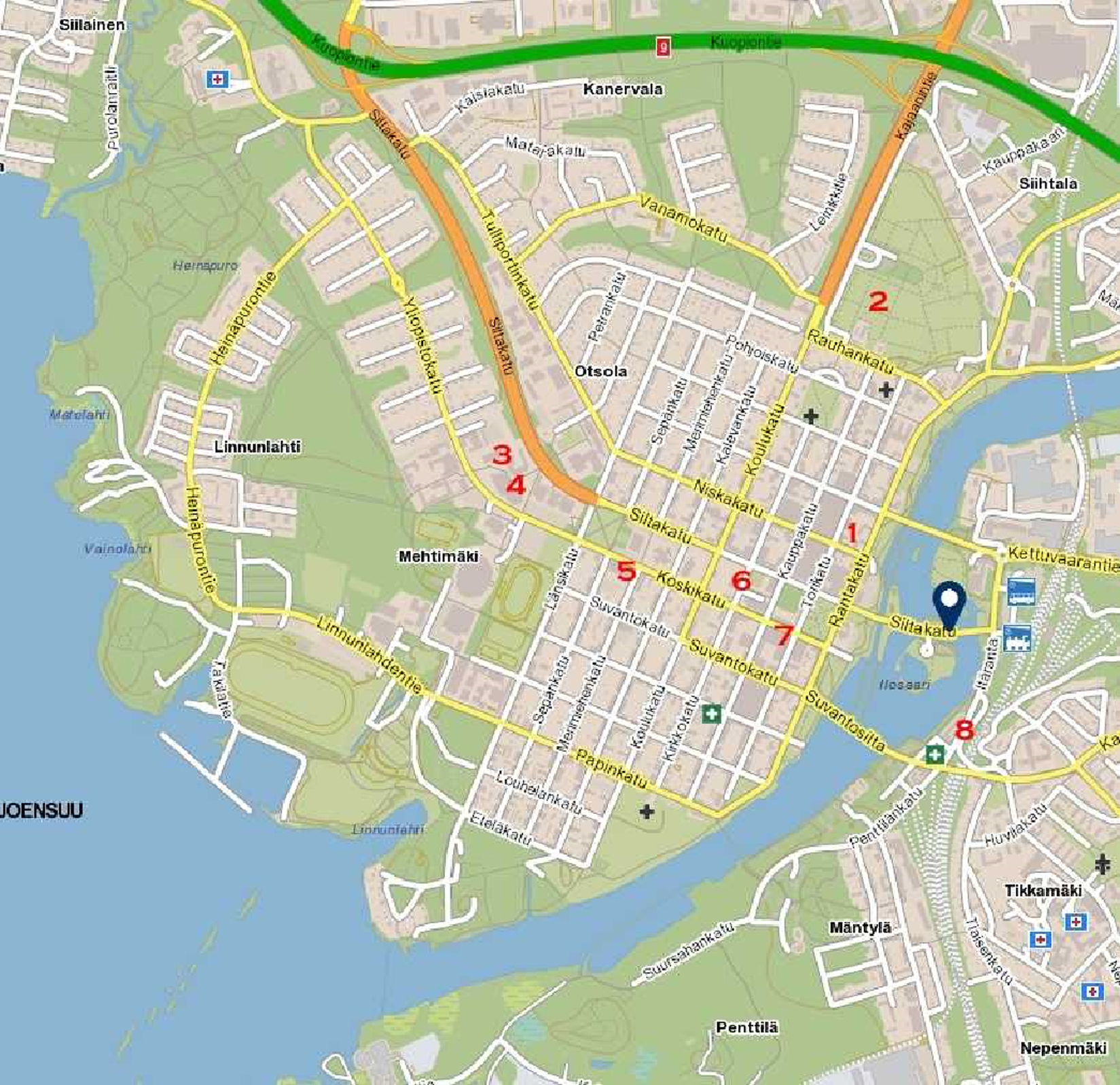

The life history of Lilija Šica related to the countryside in the southeast part of Latvia – Selonia, a particular cultural and historical region. The multimedia composition allows us to follow Lilija’s childhood memories. It is supplemented with illustrations and photos from a broad time period – from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 21st century. At the first meeting it turned out that Lilija is a very active person. Despite being in her 90s her loom was prepared for weaving. The current era, with Lilija in her 90s, is illustrated by photos of the colourful textiles weaved by Lilija, which is an activity she does on a daily basis. Weaving was her speciality at technical school in Riga, which she graduated after the Second World War. She still weaves to this day. She has weaved many gifts for all her family members. Lilija is proud of her grandsons, Andris and Juris Šics, popular bobsleigh drivers, who have been prize winners at the Olympic Games.She has a rich library; one of her favourite writers is Jānis Jaunsudrabiņš, born near the same district as Lilija. She feels familiar with the picturesque childhood descriptions in his novels.

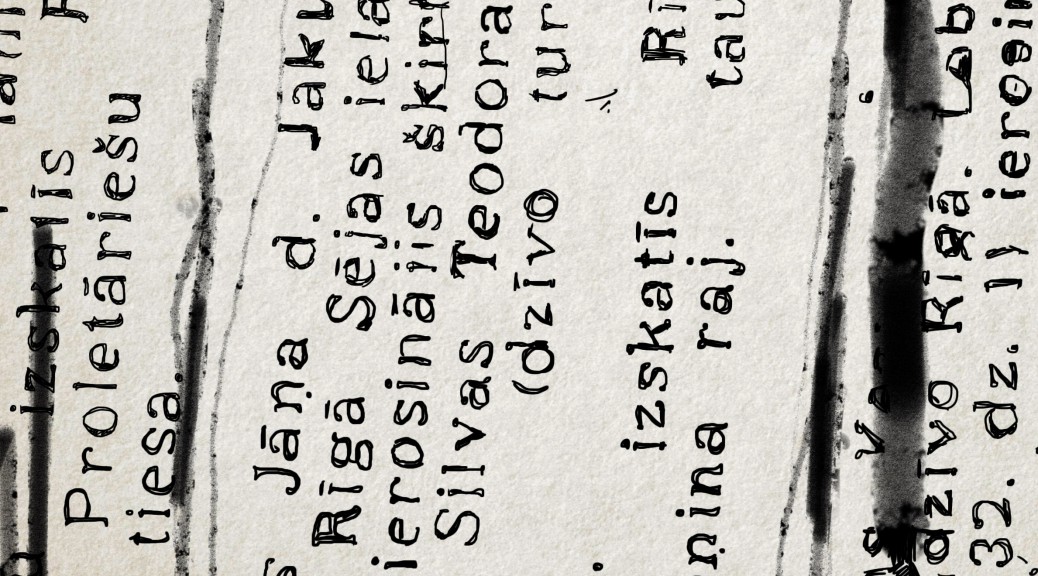

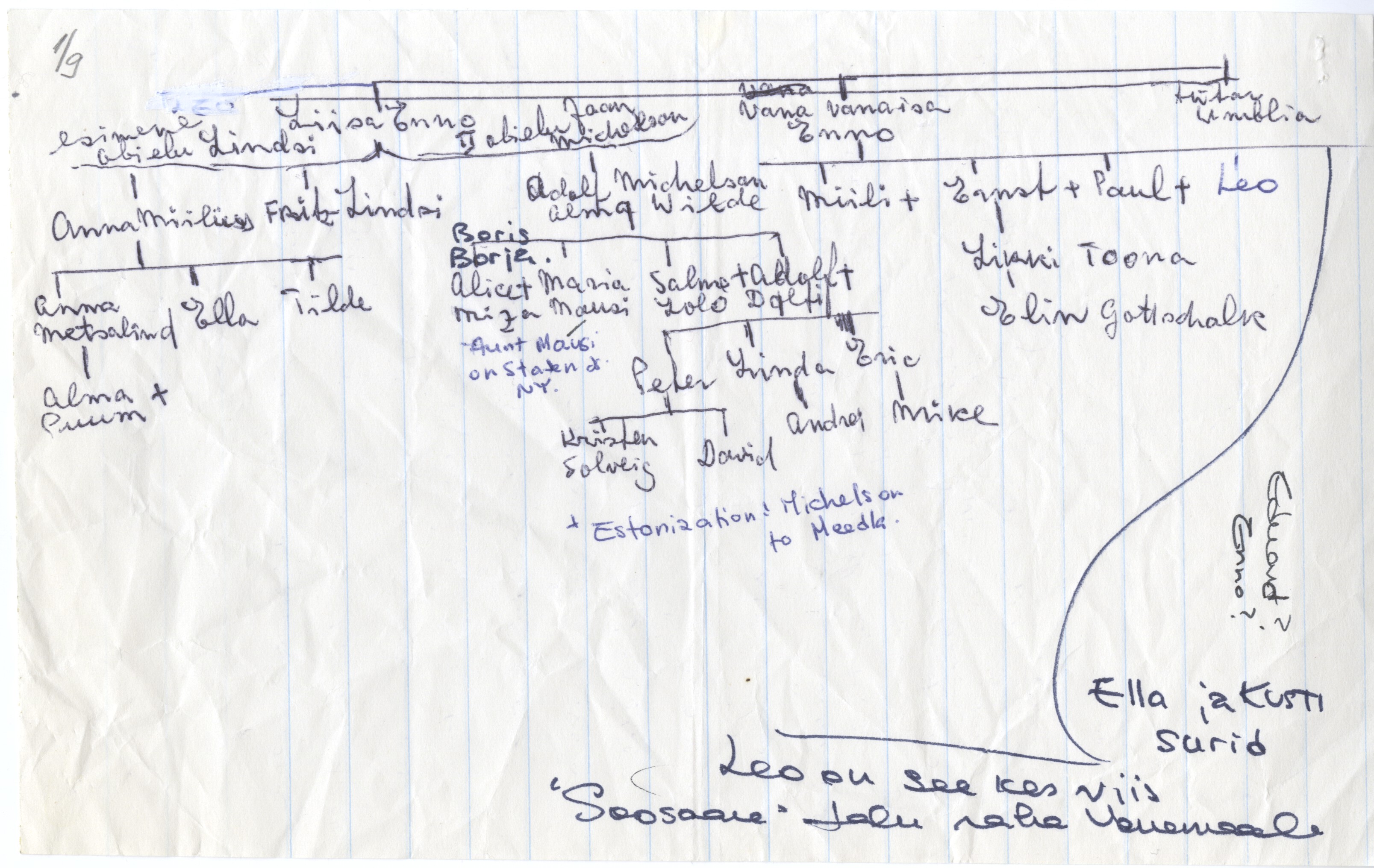

The collection of family photos added to the stories tells about various people and life trajectories, characters and relations, included in fatal thread of life and imprints Lilija’s life. All the old photos demonstrate the turn-of-the-20th-century clothing fashion style and bearing of the objects. Lilija was born at the same year (1920) when her father died. Her mother became a widow, and both of her brothers – 7 and 10 years older than Lilija – have been her babysitters. The first photo of four-year-old Lilija together with her cousin, Mega, who at that time was studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Riga, illustrates the modern haircut and dress design for them both. It was Lilija’s first visit to Riga, and we could see how perfectly the children from the countryside obtained a city style. The photo allows us to better understand changes in prestige, style and fashion during the time periods. People’s relationships are marked by arm position and posture, which changed over the years and serves as characteristics of the aesthetic taste of the epoch. Lilija’s mother had experienced a hard working life. She was religious and belonged to the marginal parish of Seventh-day Adventists. Although her sisters were rich housekeepers, she didn’t agree when one of them wanted to adopt Lilija. She was proud and didn’t ask for support from anybody. So Lilija experienced a childhood of poverty and soon trained to do various jobs at farm. Often at the springtime (at Jurģi, which is a traditional moving/migrating day), Lilija’s mother and her three children moved from one farm to another, and thus Lilija often had to change the school. We could not see great differences in lifestyle and cultural activities between the city and countryside during the 1920s and 1930s. Horses were a popular mode of transport in the countryside and cities, too. Essential changes in style and fashion happened after the Second World War. People who had previously paid great attention to their clothing and external image, had to changed their values. The value system differed in cities and countryside. It depends on changes in the social system overall. The memories written by this 90-year-old grandmother begin with the child’ view and this perspective ensures successful communication between generations. Lilija called the small episodes of her mother’s stories and her own memories a “Flash of memory”.

“Flash of memory”- drawings The painter Zanda Zībiņa had illustrated Lilija’s stories as it come from the child’s eyes. “Flash of memory” reflects situations and events meaningful for creating Lilija’s personality. She grew up together with all these people living under the same roof, and this left a vivid impression on her childhood memories. Within this social model everything important happened in front of her eyes, also death and birth. Lilija’s first education came not from schools but from the life going on around her. It consisted of characters, relations, speech and the acquiring of customs, handiwork and crafts, rites of nature. There are her brothers as babysitters, relationships between her aunts, the emigration of neighbours to Brazil to obtain land and prosperity (very common in the 1920s), her daily trek for milk, the fantasies of children, fear and inspiration, the fate of little chicks if their mother was butchered for soup, and the great wish to go to school as soon as possible. The illustrated part of Lilija’s memories reflects ordinary situations being filled with emotional values.

The life story leads from the current time to the beginning of the narrator’s life and mentions the most important moments in the maturation of the story teller’s personality. Her father’s absence welded together the members of family. Mother and both brothers participate in her story as strong background, as a sense of security for her first independent steps in adult life. We could understand the role of family as a meaningfull value, as a careful attitude toward all tales, legends and memories connected with ancestors. Lilija’s written memories finish with her marriage. The recorded life history follows after her marriage.

The video clip of Lilija’s story about the fair in her farmstead. With great emotion, Lilija tells how she had noticed the smoke, understood that her two younger daughters were on the second storey of the barn, and promptly jumped into the fire. She puts one daughter in the father arms, and then pushes down the other, and then she jumped out herself. During the accident Lilija sustained an injury to her face. That was the strongest link between the mother and her daughters. Lilija is good story teller, dancer and atractive joke master. She knows many riddles and folk dances – and these are known by every member of her big family, which includes more than 20 descendants. Thanks to Lilija’s written memories, the family history lives on into a 21st century. Lilija’s story does not convey ethical or pedagogical advice or morals; it offers one person’s real life experiences and also describes conflict situations, mistakes, failures and losses one could overcome. Memories coming from the personal level may possibly have a broader influence on society – it is possible to form a concept of national cultural identity and to point out the understanding of family as a value not only in the past but always. Family histories reflected in life-stories open up the relationship between generations and transmission of skills, patterns, opinions and cultural heritage from parents to children and even further to grandchildren and great-grandchildren. The case of Lilija’s story is a pattern of cooperation between generations, which is one of the sources of authentic Latvian culture.

Creating a Family History: One Day Training Session for Adult Education

Memory stories and the way they express attitudes towards events within the family circle show the big role of family towards the self-assessment and self-realisation process of an individual. These stories also serve as an announcement of oneself to the world. By remembering the stories and legends of the difficulties one’s ancestors have overcome, one also starts to trust his own skills and abilities. Through the memory stories of previous generations, people gain support in times of need as well as inspiration for continuing the traditions in the future. Within the family, storytelling and legends have an educational role because they strengthen self-confidence and identify common values. Even negative experience, if turned into a story, acquires a moral sense. This especially applies to the memories of the events dedicated to the family history.

A proposed training session, “Creating family history”, is provided for everyone who wants to start doing own family history. The training session includes insight into how to conduct a family history using oral history methods: why, how and when to start; doing biographical interviews step by step; what kind of additional materials can be used; and how to make for the project public if one wishes to.

The main target group:

- School and University students; adults and seniors

The goal of the training session:

- To encourage people to make their family history – everyone can do it – and why it is important both at personal and national level;

- To provide knowledge about family and oral history opportunities in the sense of researching cultural identity;

- To provide practical step by step information and skills about how to conduct family history by using oral history and biographical interviewing;

- To discuss ethical issues that might arise during and after the family history project, especially if it is published.

Sources used:

- Life stories and other sources from the Latvian National Oral History Archive (LNOH);

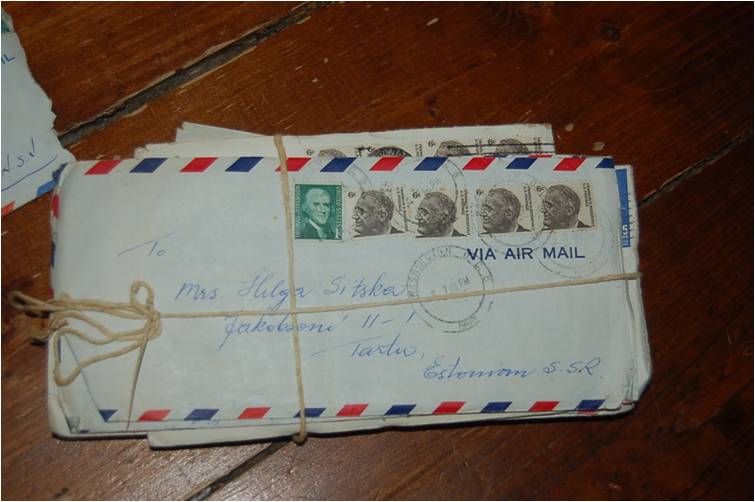

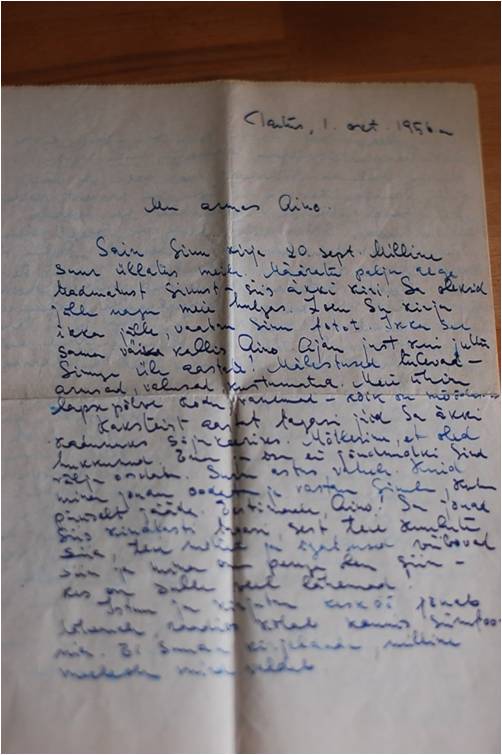

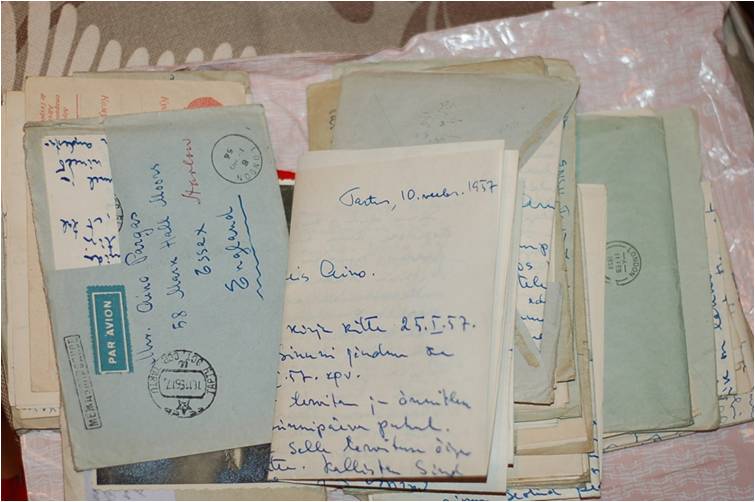

- Biographical interviews, written materials: diaries and correspondence by Lilija Šica; photos and video materials.

Structure of the training session:

Part 1:

- What is family history and why it is important to interview one’s family members: transcultural and transgenerational aspects;

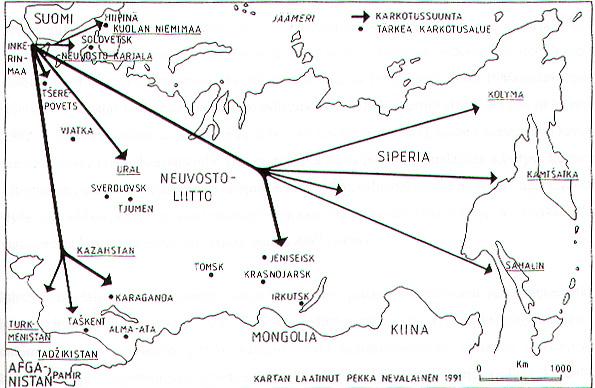

- Family history relationships with local and national history: the importance of individual and/or marginalised voices (historical background, role of oral history in post-Soviet countries, including the Baltic States);

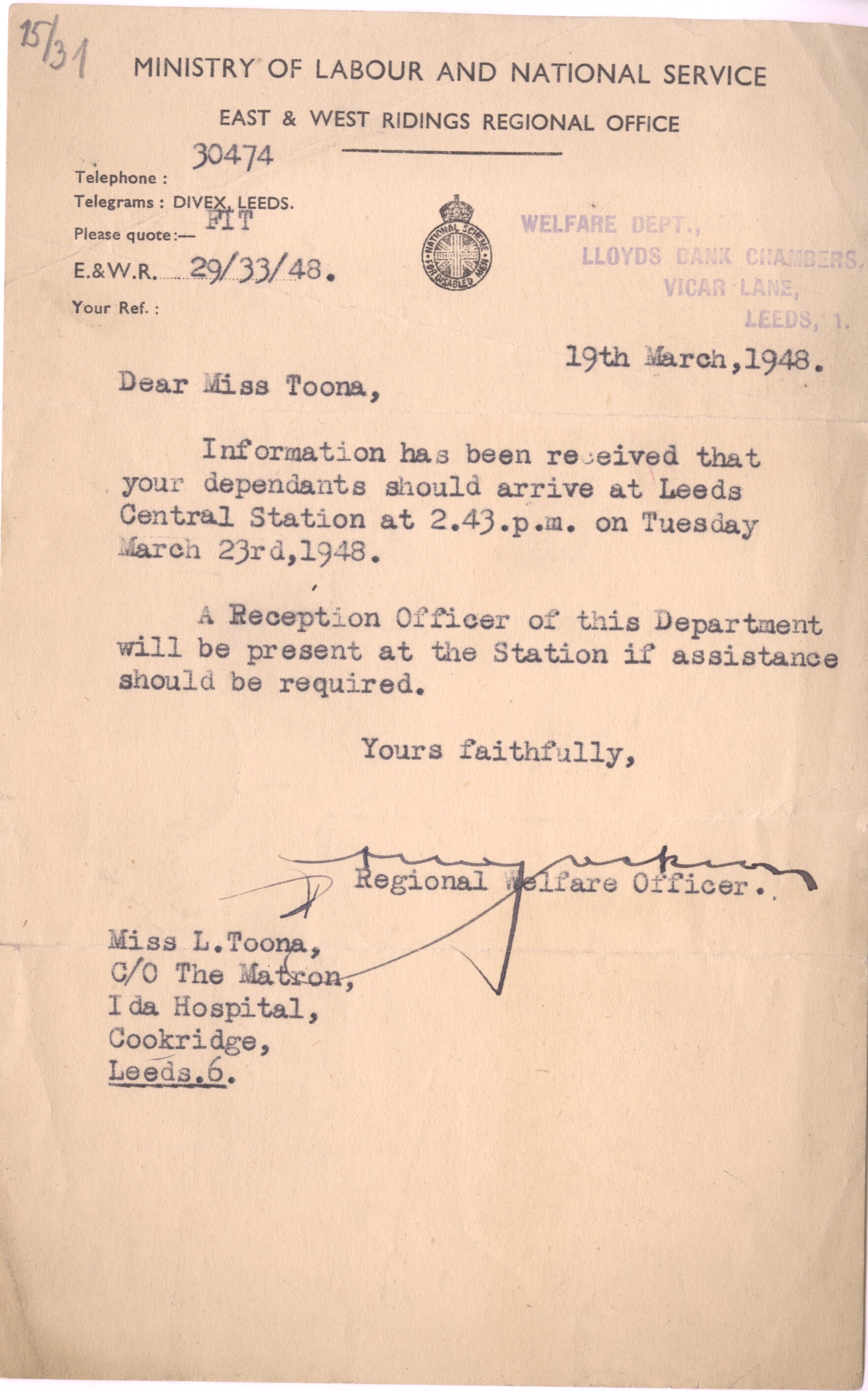

- Family history forms: interviews, diaries and letters, autobiographies, a collection of family traditions and folklore (songs, narratives, recipes, wedding rituals, etc.), photo and document albums, etc.

- Family history opportunities and limits: potential research directions (examples from LNOH): (1) family portrait in life stories; (2) family history with regard to flight, exile and change of political regimes; (3) absence of family history due to political cataclysms, repressions, wars;

Part 2:

- Defining biographical interviews – life story or life history – and how to use them to achieve various goals;

- Doing biographical interviews and family history step by step: how to prepare, how to create an interview (lists of topics and questions that may be used in interviews), what to do with an audio recording after an interview, how to transcribe it and how to edit it for public presentation.

- Writing skills and approaches of memory writing (description, characteristics; how to overcome ” white sheet fear”). Examples of sources.

Part 3:

- Introducing the audience with Lilija’s story; its biographical, cultural and historical context; the aim of writing: goal and the target group (family, extended family, wider society); what was the main focus of her performance; and what can be learnt from her story in transcultural and transgenerational aspects;

- The goal of the interviewer; collaboration between narrator and interviewer: expected and unexpected results; various types of publication (book, multimedial presentation);

- Ethics and agreements between the author and interviewer and text editor – the responsibility of respecting the narrator’s or author’s rights at all stages of listening to a person’s memories and preparing to publish them. Examples of how to form written agreements with the narrator or author of a life story regarding the preservation and further use of his or her story.