by Rutt Hindrikus.

We all remember our own personal past. It lives in our memory in the form of an hazy story or a cluster of stories. Converting such a cloud into a narrative is often very difficult and complicated. Photos are sometimes like little ready-made narratives of family history.

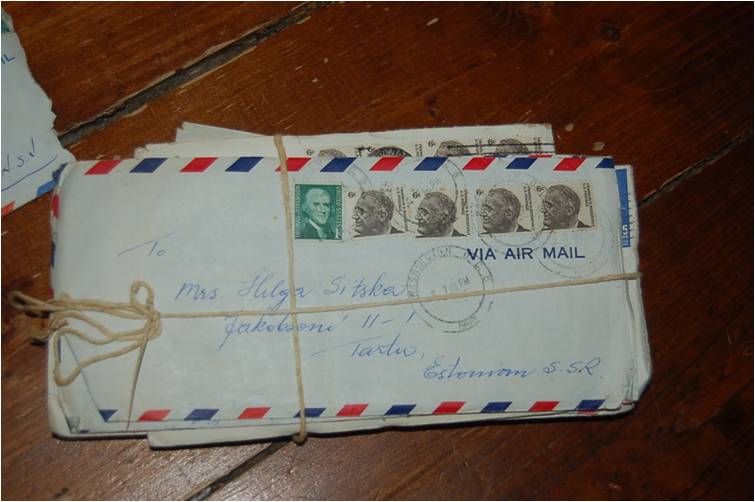

Elin: is the central figure of the story. In the archive there are many photos of her mother, grandmother, relatives, and an old photo of her grandfather in his student days with his brothers and parents.

Who are the members of Elin’s family ? Herself, her mother and grandmother, three women of different generations.

Elin’s grandfather Ernst Enno (1875-1934) was and Estonian poet, journalist, and teacher.

He married Ella Saul in 1909. In November 1910 their daughter Liki was born.

Liki married Enn Toona.

Elin was born in Tallinn on July 12th 1937.

FOTO Elin’s birth certificate

Elin: „At that time I did not know anything about my grandfather, the poet. I knew him only as “black Papa” by the dark, stern profile he presented a top his statue. When my grandmother and I walked around Haapsalu, we often stopped by the statue (on the Evening Lagoon) to rest our legs. Hers were old, mine were short. We tired easily. Sitting there countless times, my grandmother told me about “Ernie”, who had died young because he had had a “poet’s soul”.

FOTO EKLA…28548 Ernst Enno’s monument _Black papa

Elin seldom saw her parents. They were actors. Elin lived with her grandmother Ella Enno, who was an artist. She had studied painting in Tartu and in 1913 and 1914 at the Atheneum in Helsinki, Finland.This was unusual for women in Estonia at the beginning of 20th century. She “lived” for her art. Elin recalls:

I lived in Haapsalu with my grandmother, whom I called Mämmä and her sister, my great-aunt Alma, whom I called Tätä.

We were always together, my grandmother and I: weeding in the garden, /—/, walking along the Promenade , or going to the open air market.

We had a grand piano in the living-room, /—/ There was always someone playing the piano. We lived quietly, slowly and harmoniously to the strains of Chopin, Beethoven, and Bach.

Elin’s father was an artist through and through; he was a good man, but not a family man. He had risen to the very top of his career in theatre.

Elin’s memoir: I grabbed a handful of grass and ran into the street after him. When I reached him I stuffed the grass into his jacket pocket.

“What’s this,” he asked?

“Nothing,” I told him seriously. “But when you next put your hand into your pocket you will remember that you are my father and that you have a daughter.”

When I came back to Estonia in 1990 I heard that my father had kept a small plastic bag of dried grass on his desk, all of his life

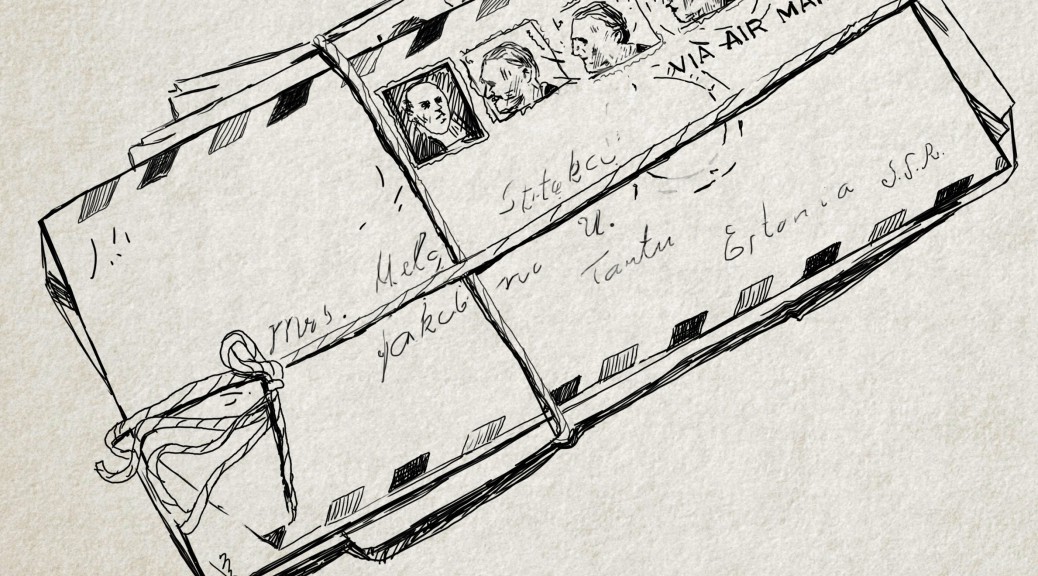

In the fall 1944 ELIN’s mother and grandmother with Elin fled to Germany, Elin’s father has not come with them because he has a new family.

After the war ended there were about 7 million refugees in Germany. Most of them were dispersed into displaced persons camps. Elin’s mother, grandmother, and Elin ended up at Meerbeck, near Hannover.

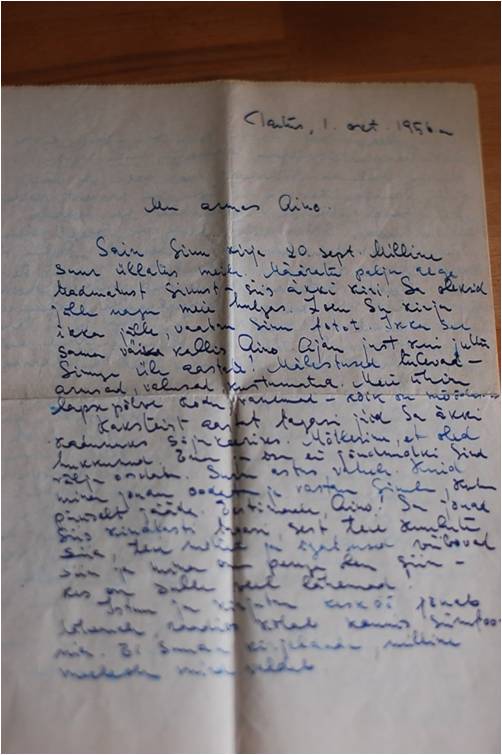

We all remember our own personal past. It lives in our memory in the form of an hazy story or a cluster of stories. Converting of such a cloud into a narrative is often very difficult and complicated. It seems to me that photos are the easiest to describe, and for structuring a life-story narrative, photo albums are the best. They are sometimes like ready-made narratives of family history.

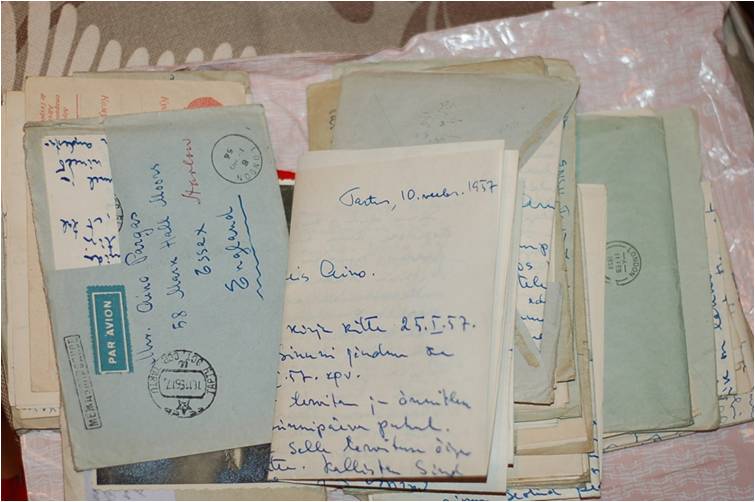

What I mean by family story is a text or cluster of texts that centers not on an individual but the story of a kinship network or the stories of many representatives of the same family. I see two ways of writing a family story: first, one narrator gathers together the stories of many people, either by recording their different voices on tape, or assembling the thoughts and views of various family members as seen in their letters or other autobiographical texts. The result is the collective „I“, an entity consisting of different points of view. The other possibility is that one individual writes down the biographies of various family members as longer or shorter narratives, but presents them all from one narrative point of view.

Elin’s life story begins with an account of her first trip to Estonia. She knows the previous generations in her family through their stories told for several times. All the stories are connected with Estonia.

Who are in Elin’s family ?/kes moodustavad Elini perekonna/ Mother and grandmother, the three women of different generations.

In Estonia she has relatives –the most important was aunt Alma(grandmother’s sister).

Grandmother has told very much about the other relatives who were already dead or lived somewhere in Estonia. All these stories were parts of Family history. There was a very important person – her grandfather –actually it was Grandfather’s statue, Black Papa.

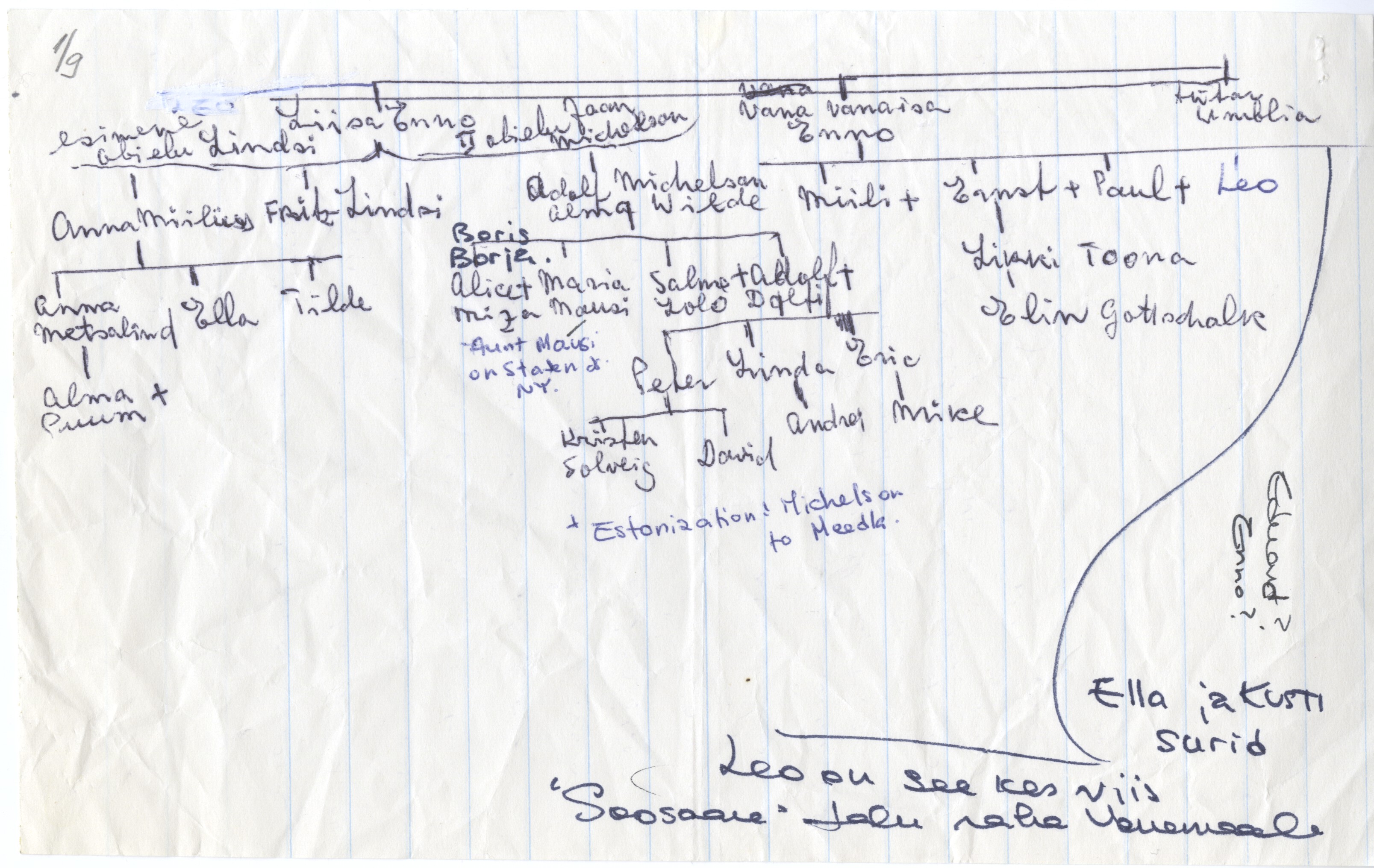

Elin’s case is a special case. She fulfilled her wish to write her grandfather’s history . Monograph’s (?) title is Rõõm teeb taeva taga tuld, it is a verse from Ernst Ennos poetry. We can see this book as a ideal family history. IT starts with chapter Ennode päritolu ja perekond and ends with Family tree. It consists all kind’s of rumors and legends what were told in family, the most intriguing among them was the rumor, that local baron was the real father of one predecessor.. Such cases were not rare but such rumors are very common too.

Sellejuures on see raamat korralik kirjandusajaloolisest traditsioonist lähtuv biograafia

A book of that kind needs much more archival sources than we have demonstrated.

But that book is itself an archival source for the new generationes.

Elin’s story is a good example to speak about war and peace and about life in different countires..

After the war ended in 1946, Elin her mother and grandmother ended up at Meerbeck, near Hannover. The camp was actually a village which had been turned into a DP Camp as punishment for the villagers. (It happnes in the British zone).

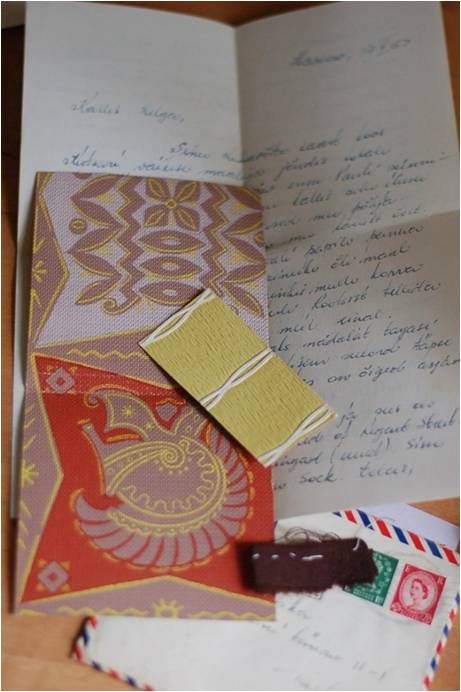

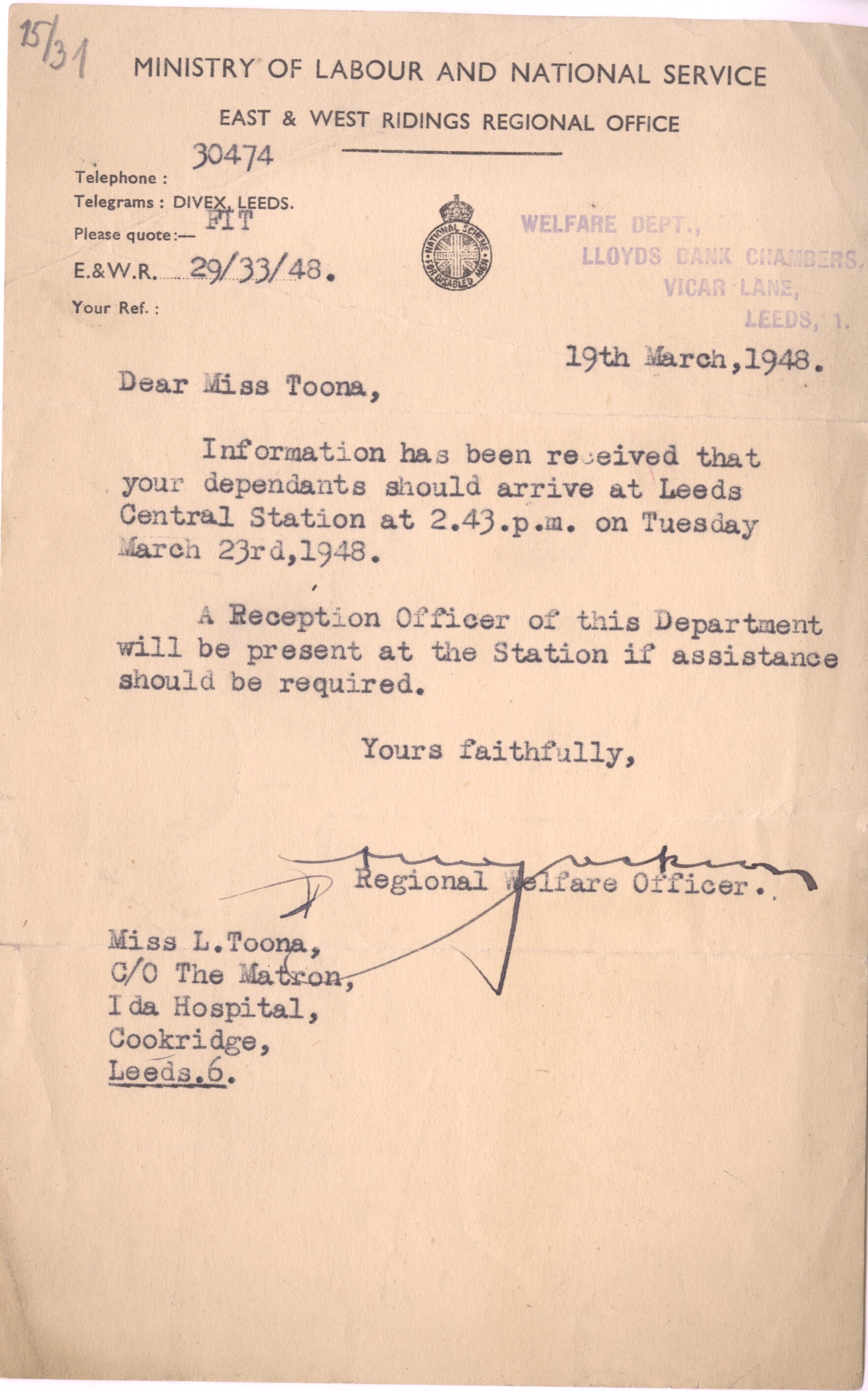

In May of the year 1947 the mother signed an contract to work in an English hospital. The questions regarding that period of Elin’s life (like why was she living in the hospital woods and why was she not allowed to further his education?) – was cleared up in 1999 when she was reading old newspapers and came across articles that had been written at the time her mother went to England. “ Newspaper “Eesti Teataja” on 5th February 1947 wrotes “Baltic Swans fly to England” The jobs were for women between the ages of 18 and 45 in hospitals, sanatoriums, orphanages and nursing homes. Mother signed up for five years. Gandmother and Elin remained in Meerbeck until March 1948, when grandmother also signed up (she was 69 years old by then), to work in the hospital sewing-room. The hospidal was Ida Hospital, Cookridge, Yorkshire.

One of the characteristics of exile is the loss of one’s previous status. English society was very hierarchical, and the “fall” was very steep for most of the refugees. . Nobody knew about Estonia or where it was, this country did not exist. And, as it did not exist, the labourers from there were simply liars. Elin very well remembers such attitude towards them.

At that time, the so-called Eleven Plus exam segregated children into two groups at the age of eleven. Any child who did not pass the 11+ exam was denied further education. Elin arrived in England in March 1948; the test was held in two months, which was too short a period for learning the language. Her new homeland designated her for the labour force

Starting at the age of 15, Elin had to work at a textile mill together with other foreign workers. For the next three years she got up half past four every morning. She secretly attended some educational courses and received a stipend to an acting school in London. This was a private school, since public education was still closed for her. She found work in TV and got some film roles. Finally, she could leave the hardships behind, and she also got rid of her Yorkshire accent. In a few years she was even able to find a good position in the BBC.

In 2008, Elin Toona published a book about her grandmother with title Ella. Despite the radiant figure of Ella Enno , it is a sad book. For the first time, Toona is talking about the events in her life she has never before touched upon or which she has only briefly mentioned. Toona’s private life has had some crazy turns, she has twice been married to a millionaire. The first time, she escaped from her husband after a few weeks of living together in Hong Kong. Her husband’s family had threatened her and she realised that she did not fit into the lives of rich people of this kind. During her escape through India and Iran she met an American journalist who became her second husband; with him she liveed in the USA. She is not yet ready to write detailed memoirs of this period of her life. These problems can still be found in her fictional text, and it is not difficult to realise that the hidden autobiographical undercurrent in The Last Daughter of Kaleviküla originates from this period. After the death of her second husband, Toona lived for a while in a camper in Florida, had a job and spent time writing. The title of her latest book is Into Exile.

She recalls: As a child of refugees, I had no role models for a conventional life or a proper family. People married to get to America or Canada, they put their “bread into one cupboard”, to live cheaply.

HER best friend was her grandmother.

About her mother she writes: I did not know my mother until I was an adult. We had lived together only briefly and as a child I had always referred to her as “my friend”. We became really good friends in London and very close until she had her first stroke in the summer of 1975.

Elaborate pedagogical relevance on the resource, relating it to one or more pedagogical cotext:

High school, adult education, museum education. concrete plans how this material can be used for teaching

Küsimused: kes on Elin Toona (tekstist lähtudes)? Miks ta põgenes kodumaalt ? Miks oli Elini kõige parem sõber ta vanaema ?

Missuguse perekonna lugu peaks käsitlema enne kõike ?

Otsige Google’it kasutades internetist Elin Toona kohta 6 lauset.

Otsige välja Elin Toona raamat „Into Exile „(2013), mida majandusväljanne „ The Economist” peab 2013 aasta parimate raamatute hulka kuuluvaks.